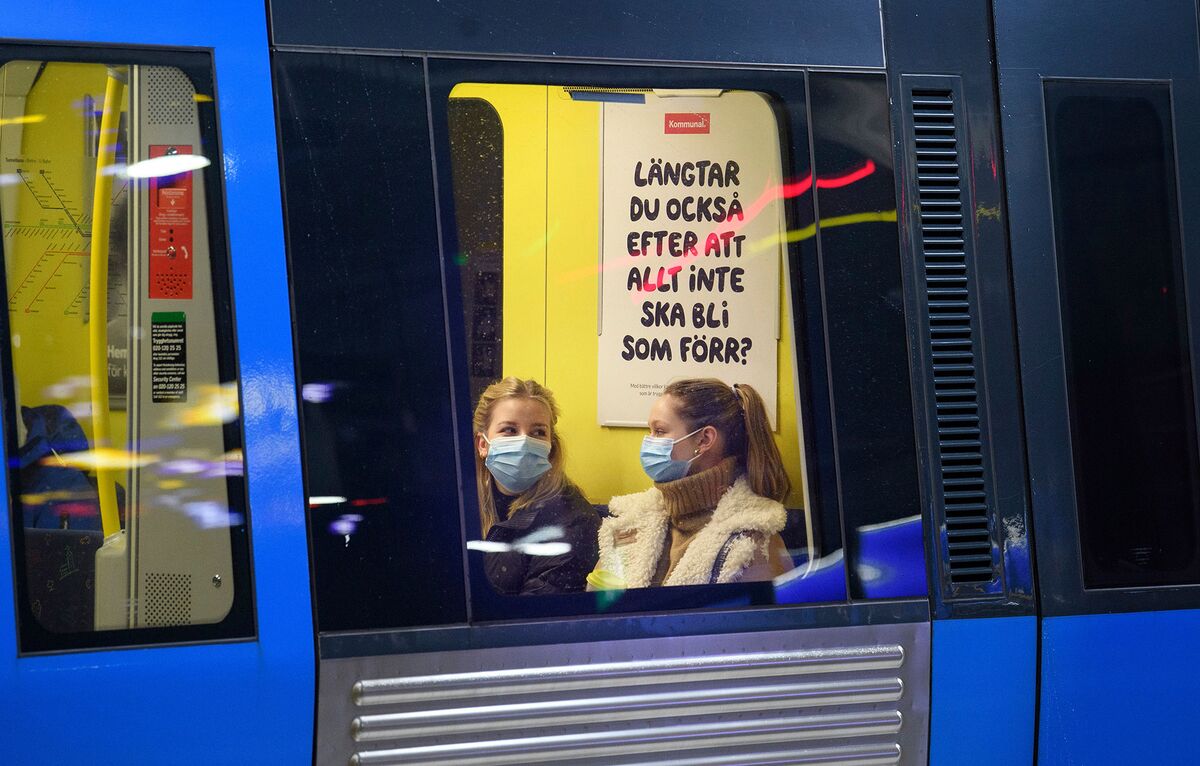

Passengers in an underground train in Stockholm.

Photographer: Jessica Go / AFP / Getty Images

Photographer: Jessica Go / AFP / Getty Images

Sweden’s practical response to Covid-19, which avoids exclusion while imposing restrictions, has sparked controversy from the outset. Although mortality rates rose in early 2020, Sweden kept shops, restaurants and most schools open. It did ban public gatherings of more than 50 people and some restaurants were ordered to close temporarily, but most measures had little legal weight. While many people initially complied with it, they were less willing when the second wave occurred in November, which forced stricter measures.

1. What arguments gave rise to this?

Lockdown skeptics see the strategy as a way to avoid negative side effects of restraining the transmission and as a model to contain the virus without violating personal freedom. Critics describe it as a deadly folly or utter folly disaster. Supporters of the government point to countries such as the United Kingdom, Italy and Spain that have closed but have higher death rates than Sweden, while critics claim that the best comparison is with neighboring countries such as Finland and Norway, which have similar population densities and health care coverage, but of which the mortality rates and infection levels were considerably lower than those of Sweden.

2. Why did Sweden not lock up?

Anders Tegnell, Sweden’s state epidemiologist and chief architect of the response, argued that all aspects of public health should be taken into account, including the detrimental effects of restricting people’s movements. Tegnell said that Sweden had followed proven methods for dealing with pandemics, while other countries’crazy ”when locked. Rather, Sweden relied primarily on people’s willingness to voluntarily adjust their lives to limit transmission. There are also legal restrictions on the measures that Sweden can take; while a is a temporary rule that allows the government to close shops, there is now Swedish legislation that does not allow stay-at-home vouchers or curfews.

3. Was the goal to achieve herd immunity?

The Public Health Agency initially assumed that immunity in the population would eventually stop the transmission of viruses, although it denied the media reported that the aim was to achieve herd immunity by infecting the population. Herd immunity, which blocks transmission, occurs when enough people in a community are immunized by infection or vaccination. Early calculations overestimated the number of unreported cases, which led experts to misjudge the level of protection in the population. Tegnell said in early May that at least 10% to 20% of the people in Stockholm were infected, while the agency found three weeks later that no more than 7% of the capital’s population antibodies against the virus. When the second wave hit, Tegnell and his colleagues made it clear that Sweden could not rely on herd immunity to stop the virus from spreading.

4. Is it more about politics or science?

In Sweden, authorities such as the Public Health Agency have a great deal of autonomy, and although the government has the final say, it tends to rely heavily on their expertise. When the pandemic struck Sweden for the first time in March, it was clear that the center – left government of Prime Minister Stefan Lofven would follow the agency’s approach, and it continued to do so, even though the initiatives taken since November taken, some signs of a fracture are shown. While Lofven has said in public that he is still making decisions based on consultations with Tegnell and his agency measures since November point to a more active government role.

5. Has the strategy been abandoned?

Partial. From November 2020, Sweden began to introduce more significant restrictions, which in early 2021 included a ban on alcohol sales after 20:00 and that schools could teach the seventh to ninth grade online. While stores remained open, there were capacity constraints. Most entertainment venues, such as cinemas and theaters, were forced to close because there was a canopy of eight people. The Public Health Agency has also adjusted its recommendations by quarantining people who are infected and making mask recommendations, although only during peak hours on public transport. Yet there was no formal exclusion. The Oxford Coronavirus Government Response Tracker, which is expanding information on worldwide policy on virus control and lock-in, health care and economic support measures, showed that Sweden, in early 2021, is moving towards the least stringent approach in Europe by the end of March 2020. has. to the middle of the pack.

Not exceptional

Sweden’s Covid measures are now just as strict as in most of Europe

Source: Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracking

6. How bad is Sweden’s death rate?

At the end of January 2021, there were more than 11,500 people in Sweden died, or 113 per 100,000 of its population. It was above the EU average, the triple death rate from Denmark and ten times that from Norway. The countries worst affected in Europe, including the United Kingdom, the Czech Republic and Italy, registered more than 140 deaths per 100,000. The pandemic exposed flaws in Sweden’s institutions and healthcare system, similar to those elsewhere. Nursing homes were poorly prepared, the country had insufficient supplies of protective equipment, a lack of coordination hampered testing efforts, and the capacity for intensive care was less than half the European average. Sweden was also one of several countries that underestimated the rate at which the disease would spread and acted too late.

Lethal transmission

Sweden’s mortality rate is higher than the EU average, lower than in the US

Source: Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg

7. Did the strategy achieve any success?

Proponents argue that Sweden has shown that it is possible to control the virus without taking steps that restrict freedom and adversely affect health. Although the World Health Organization does not endorse Sweden’s strategy, it has emphasized the benefits of measures based on trust between authorities and the public. The recommendations issued during the early stages of the pandemic influenced people’s behavior, with sales of Stockholm restaurants by the end of March between 75% and 80%. After the December holidays, when many people stayed home, there was a decrease in infections, but the authorities warned that Sweden would see a revival unless people took the guidelines for social distance. There were also concerns about new variants of the virus, which asked the country to restrict access to the United Kingdom, Denmark and Norway.

The reference shelf

- Bloomberg Opinion’s Lionel Laurent on how Sweden’s second wave offers a hard track reality check.

- A Bloomberg opinion piece by Justin Fox on what it takes to get herd immunity.

- A Take a quick look at why the mutated coronavirus variants are so worrying.

- The regulations of the Swedish Public Health Agency and guidelines to prevent Covid-19 transmission.

- A Bloomberg article from Tegnell’s from June 2020 assessment of strategy.

- ‘A interview from Anders 2020 with Anders Tegnell on Sweden’s strategy.

- Correspondence in the Lancet by former state epidemiologist Johan Giesecke defending Sweden’s strategy. His assumption that between 20% and 25% of Stockholm’s population was infected in early May was interviewed by several critics.

- A report of the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences, which is contrary to the view of the Public Health Agency that there is no reliable evidence to support the use of face masks.

- A report on how Sweden’s elderly care system handled the pandemic, compiled by a commission appointed by the government.