Joseph V. Micallef is a best-selling author of military history and world affairs, and keynote speaker. Follow him on Twitter @JosephVMicallef.

In 1972, President Richard Nixon paid an official visit to the People’s Republic of China. The visit, which had been in the planning for several years, resumed the resumption of direct diplomatic contacts between China and the US after a quarter of a century of political isolation.

The thaw culminated in 1979 when the US entered into full diplomatic relations with China.

Nixon’s visit was motivated by a desire to gain more leverage in US relations with the Soviet Union and to secure Beijing’s assistance in negotiating a peace agreement between North Vietnam and South Vietnam. The voyage was also against the backdrop of increasing Soviet power around the world, especially the dramatic growth of the Soviet blue water fleet and Moscow’s strong support for subversive movements around the world.

The revelation to China also took place at a time when Soviet-Chinese relations were deteriorating. The situation was underlined by repeated military clashes between China and the USSR, along the border of the Ussuri River between the two countries, in 1969. There were widespread rumors at the time that Moscow was considering a nuclear strike against the Chinese nuclear test facilities in Xinjiang. Amid a rapid build-up of Soviet military forces along the Sino-Soviet border, Chinese leaders concluded that the USSR posed a greater threat to China than the US.

Nixon’s dramatic appointment with the Chinese was described at the time as ‘playing the China card’, a term now captured in history books.

Fast forward half a century later. China and the US have now become each other’s main opponents. They are engaged in a wide range of military, economic, technological and diplomatic competition around the world.

Russia, the successor to the Soviet Union, no longer commands the global superpower status once enjoyed by the USSR. With an economy smaller than that of Texas and heavily dependent on the export of raw materials, mainly oil and gas, it has little prospect of regaining status.

However, Moscow still recommends a substantial army, can project significant military force along its periphery, and maintains a large nuclear arsenal between continental and an extensive military-industrial-technological complex.

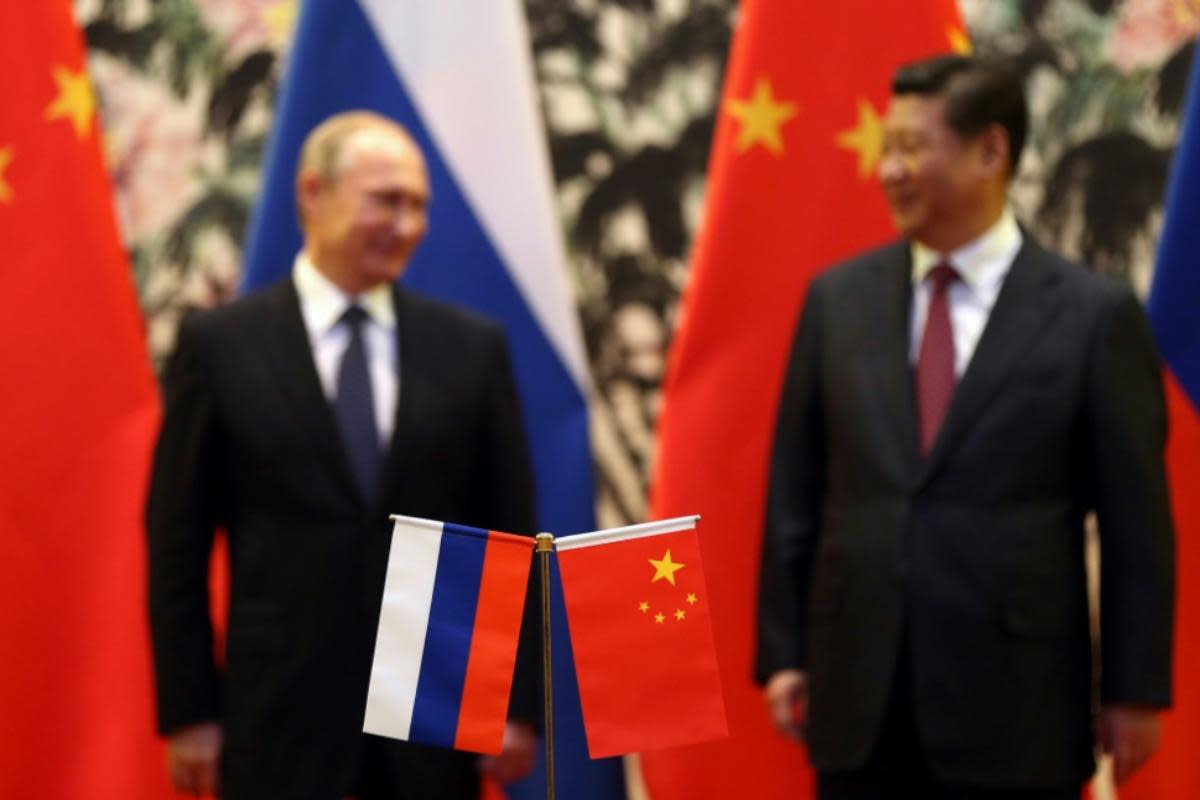

Now that Russia is the weakest country in the US-China-Russia triumph, will Russian President Vladimir Putin try to play his own ‘China card’ to find leverage against the US?

Russia and China

Over the past decade, Moscow has significantly expanded its economic relations with China, which is now the world’s largest importer of oil and gas. It usually ranks in the top three global importers of most commodities. As one of the world’s largest exporters of hydrocarbons, it makes sense for Russia to seek new markets in China, especially as the ability to expand its energy exports to the European Union (EU) has been hampered by the US and European sanctions imposed on Moscow following its 2014 seizure of Crimea.

These sanctions also blocked access to capital of Western financial institutions, and Moscow increasingly looked to Beijing for funding its energy and other resource development projects. Chinese capital, for example, has played a key role in funding the Yamal LNG project and will play a key role in underwriting Gazprom’s $ 55 billion Power of Siberia gas pipeline. This project will develop the Chayanda and Kovykta gas fields in Yakutia and build a pipeline to transport gas to Heihe in Heilongjiang, where it will join the existing Hehe-Shanghai pipeline.

Beijing has included the Northeast Passage maritime route across Russia’s various Arctic seas in its broader development program for the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) infrastructure, calling it the Polar Silk Route.

Moscow also played a role in modernizing China’s military. Historically, China was one of Russia’s largest arms customers, second only to India. In 2018, China accounted for about 14% of Moscow’s arms exports, amounting to about $ 15 billion.

Russia has supplied the Su-35 multiple fighter to China. The Su-35 carries both guided and unaccompanied air-to-air and air-to-ground missiles, as well as conventional and smart bombs. The two countries are also working together on the development of a heavy lift helicopter for military use.

And the Kremlin supplies China with six S-400 long-range air defense systems. This is the same system that was recently purchased by Turkey. The Russian systems will contribute to the existing air defense network in China. The implementation of the S-400 could enable China to create an airport across the Strait.

Russia is also helping China build an early warning system to identify intercontinental launches with ballistic missiles. Currently, only the US and Russia have this capability.

Russia and China have also expanded the scope of their joint military exercises. Prior to 2018, these joint exercises were around scenarios against terrorism. Starting with the Vostok 2018 exercise, the joint exercises now emphasize joint defense and counter-attack training and coordination.

Play the China card

Putin was not ashamed to abandon hints that he would consider a more formal alliance with China. On October 20, during the most recent meeting of the Valdai Discussion Club, Putin, when asked about a potential military alliance with the VRC, replied: ‘It is possible to introduce yourself. We did not set ourselves that goal. But in principle, we are not going to rule it out either. ‘

The Valdai Discussion Club is a think tank and discussion forum in Moscow, established in 2004. It was often used as a place to indicate changes in Russian policy or to launch test balloons.

On the other hand, despite the benefits of greater Sino-Russian cooperation, long-term Russian and Chinese interests differ significantly.

While China has accommodated Russia within its BRI, the program is contrary to Russia’s long – term interests. If the BRI is successful, the former Soviet states of Central Asia, the so-called “stans” (Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan and Azerbaijan), will move to China’s economic trajectory and presumably also in its political and diplomatic Lane.

Moscow intended to reintegrate these former Soviet republics into its Eurasian Economic Union, a customs union and common market, and to utilize its geographical access to European energy markets to gain transit fees and political advantage for the export of Central -Asia’s energy sources to Europe. However, if energy exports go east to China, Moscow will have far less leveraged funding over the ‘halt’, even if it can provide access to existing Russian pipeline and railway infrastructure in the short term. In the long run, however, the countries will compete directly with Russia to export hydrocarbons to China.

Although the Sino-Soviet border agreement in 1991 apparently settled the border dispute between the two countries, Chinese historians, with the tacit approval of Beijing, continued to criticize the “unequal treaties” that existed in the 19th century between the Russian Empire and the Ching Dynasty is signed. that the disputed territory should be returned to China. The Treaty of Aigun (1858) and the Treaty of Beijing (1860) transferred approximately 600,000 square miles of Chinese territory in Manchuria and western China to Russian control.

At the 18th and 19th Chinese Congress of the Communist Party, for example, Chinese President Xi Jinping called for ‘restoration of sovereignty over Chinese territories lost by the introduction of unequal treaties by hostile foreign powers’.

In addition, there are currently millions of Chinese immigrants, legal and illegal, in Russia’s Far East. Moscow has wrapped up the Chinese migration cloths, partly because the region is suffering from chronic labor shortages, and also because much of the legal immigration has been linked to Chinese investments in the Russian Far East.

Russian residents of the region have argued that the illegal migration is a de facto Chinese invasion and have expressed concern that Beijing intends to take back its historic territory and possibly more. These concerns were underlined in a 2015 film by local filmmakers, “China – A Deadly Friend”, which became an internet sensation in Russia and was widely watched.

However, it is not clear what China earns from a formal alliance, military or otherwise, with Russia. Less than 2% of China’s trade is with Russia, compared to about 20% with the US. Closer relations with Russia will not move the needle in any significant way. As long as the US and the EU continue to impose sanctions on Russian energy companies, China’s demand for energy and investment capital will continue to prevail in dealing with Moscow.

A military alliance between the two countries would also be a significant liability for China, linking it to a declining power that could lure Beijing into conflicts it would rather avoid.

The possibility of a Russian-China alliance poses important challenges to the US, especially the military stance in East Asia and the Western Pacific. It is not surprising that the Kremlin will use the threat to gain more leverage against the US, and Russia is not alone in this regard either. Beijing may find it just as useful to play the “Russia card” to expand its leverage against the US

Although Russian and Chinese interests differ significantly in the long run, and in many cases do not harm each other, in the short term both countries will use an expansion of military and economic cooperation to seek more leverage against the US, partly to limit the minimum . the impact of US sanctions on any country.

Even if their cooperation stops much less than a military alliance, a continuous expansion of Sino-Russian military ties and strategic coordination is problematic for the US Chinese navy’s access to Russian ports in the Pacific, such as Vladivostok, an important challenge. to U.S. naval domination in the western Pacific.

The possibility that Beijing could coordinate a move to Taiwan with a comparable Russian move against the Baltic states cannot be ruled out either.

Even more important is the related question of whether the US should try to normalize its relations with Moscow so that it can possibly play its ‘Russia card’ in its negotiations with Beijing.

In the end, neither Russia nor China can decide to seek a formal military alliance. If you only drop tips from a potential one, it may be sufficient to get leverage. Even if Putin was willing to play his China card, it is not clear that Beijing would be willing to accommodate him.

No matter what any country eventually does, however, this card game is just going on.

– The opinions expressed in this opinion are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Military.com. Find out more about how to submit your own comments.