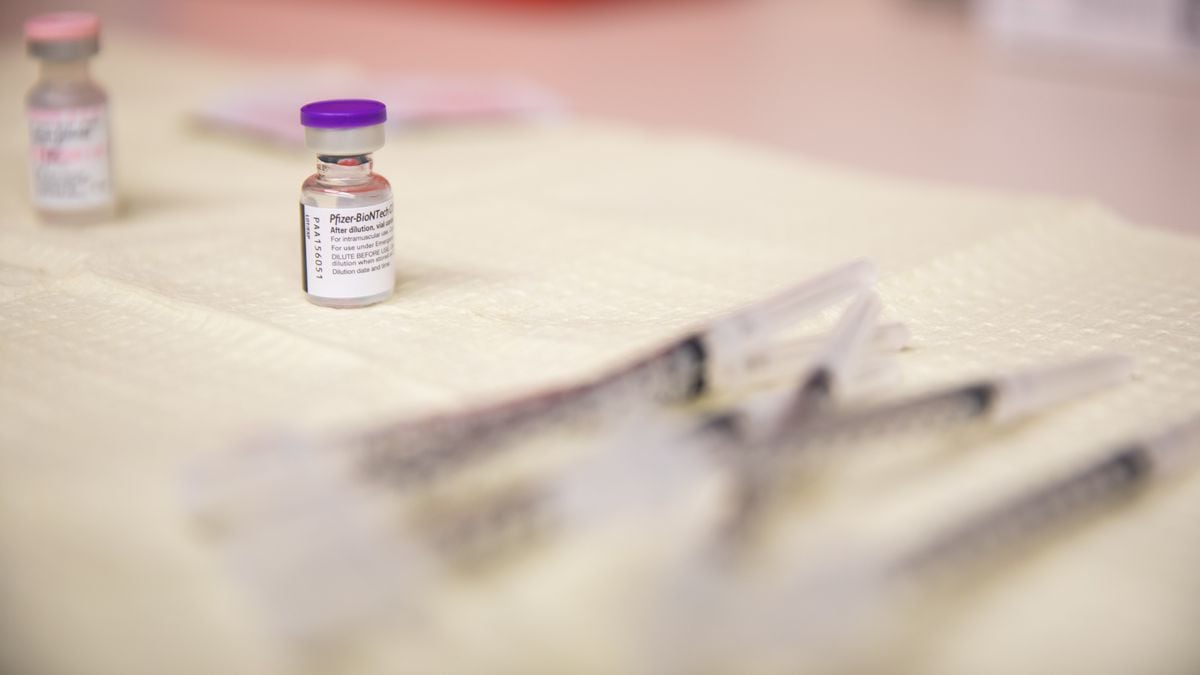

An unopened vial of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine at the Deschutes County Public Health Department in Bend, Ore., Tuesday, January 12, 2021.

Bradley W. Parks / OPB

This week, Kaiser Permanente launched a COVID-19 vaccination clinic at the Oregon Convention Center in partnership with three other major health care systems: Providence, Legacy Health and OHSU.

It is the first mass vaccination site in the Portland area and a major step in the state’s effort to build a system that could eventually expand to vaccinate more than 3 million adult Oregonians.

The conference center clinic is by appointment only and will vaccinate approximately 2,000 people a day. As more doses become available, Kaiser and his partners say the site should have the capacity to vaccinate up to 7,500 people daily.

“We envision it as a sustainable business that we will run until we no longer need it,” said Wendy Watson, chief operating officer of Kaiser Permanente Northwest. “Our ultimate goal is to keep it open 7 days a week, extended hours.”

The new website is an example of how Oregon, after a slow start, is doing a better job of getting vaccine doses out of the freezer and into people’s arms: last week, the vaccines repeatedly targeted the government, Kate Brown, of 12,000 doses per day.

But the rate of vaccination still needs to increase for Oregon to reach herd immunity and stop the spread of the virus: Just over 6% of the adult population has so far received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine.

Getting there is complicated and requires more than just large spaces to inject our vaccines. Here is what experts say the state needs to successfully scale up the distribution:

More vaccines

Each week, Oregon receives approximately 100,000 vaccinations, including the first and second doses of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine and the Modern COVID-19 vaccine. If this sounds like a lot, remember that there are about 3.3 million adults in Oregon and that each one needs two doses.

It will take approximately the current amount to fully vaccinate each adult Oregonian by the end of the fall.

Patrick Allen, director of the Oregon Health Authority, said a lack of supply is the main obstacle the state faces.

“We are now in a place where we can administer virtually as much vaccine as the federal government can provide us with,” Allen said during a press conference for the conference center clinic.

Across the country, hospital systems and other partners have increased the effort to deliver shots – and now they are begging for more doses. But the supply of the manufacturers remains limited.

“Until a new vaccine is approved, or production goes up significantly, everyone in the state, including this conference center operation, will be able to vaccinate more people than we do not vaccinate,” Allen said.

In fact, the approval of a new vaccine may soon help alleviate the supply shortage in Oregon and other states.

A third vaccine candidate, from Johnson & Johnson, is nearing the end of clinical trials. Depending on what the data shows, it could go to federal regulators in February for emergency approval.

An Army Volunteers

Oregon needs more trained inmates and more staff to support them.

Before anyone can be vaccinated, they may need help determining where to park. They must sign a consent form and investigate factors that may complicate the vaccination. After receiving the shot, patients should be observed in a clinical setting for 15 to 30 minutes in case of an allergic reaction.

All that extra volunteers need.

Health systems are tapping retired nurses and doctors to help their staff receive vaccination staff so their regular clinicians can focus on treating COVID-19 patients and anyone in need of care.

Another source of support: the Oregon Air National Guard and the Oregon Army National Guard.

Oregon has about 8,300 Army and Air Force guards. Several hundred have medical qualifications and can administer the shots, but the most important role of the guard is probably to provide logistical support and non-medical volunteers for vaccination sites.

Vaccines at the pharmacy

Pharmacies currently play a key role in giving the vaccine to residents in long-term and memory care, by bringing it directly into the facilities.

And the state and the CDC have the potential to activate a much more extensive pharmacy partnership that can deliver the vaccine directly to retail pharmacies across the state – which could be eligible for members of the public to be vaccinated for free at their local pharmacy.

The pharmacies participating in the federal program contain many well-known names, including CVS, Walgreens, Fred Meyer and Costco.

The governor said earlier this month that the state expects the shipment for pharmacies to arrive soon.

It is now unclear if this happened, or if the federal government is sending Oregon enough vaccine to activate the pharmacy program. A week after Brown said the state was launching it, she and other governors accused the outgoing Secretary of Health and Human Services, Alex Azar, of promising more doses than the federal government could actually deliver.

The Oregon Health Authority has not responded to a request for an update on when retail pharmacies in Oregon will receive the vaccine.

A plan for essential workers

COVID-19 did not affect all Oregonians equally. Business rates are more than twice as high for black and Native American Oregonians as for whites. For Pacific Islanders and Latinos, the difference is even greater: it’s more than three times as likely to get COVID-19 as a white Oregonian.

National research has found that a major reason for these differences is that specific racial and ethnic communities are over-represented in low-wage jobs that cannot be done remotely, and that they are more exposed to the virus at work.

“I would like to bring this to the forefront of the conversation,” said Daniel Lopez-Cevallos, a professor of health equity and ethnic studies at Oregon State University. “We have essential workers who are exposed there daily.”

According to Lopez, the governor should at least make it clear when essential workers are going to get vaccinated. The State Advisory Committee on Vaccines has placed them in the broader group – IB – which for some time will have preference over teachers and adults aged 65 and over, but over the general population.

Lopez-Cevallos would like to see the state plan a specific vaccination strategy for essential workers.

Melissa Unger, director of the SEIU Local 530, shares Lopez-Celvallos’ concern: the state does not yet have a purposeful plan to reach the vital workers most affected by the virus.

Unger believes vital workers are at risk of being left behind if the state relies too much on mass vaccination sites because they will not have time to wait in line, or to take refuge online in search of new appointments to be released .

“They have to go to work. “We need to make this process work for the people who have been asked to keep our economy going during this pandemic,” Unger said.

Unger’s proposals include a dedicated appointment line that enables essential workers to plan their vaccinations, and reach out better – over text and in people’s native language.

More and better communication on public health

Unger and Lopez both say the state needs a more aggressive public health message campaign to reassure people and answer their questions about the vaccine.

Unger says not all health care and hospital workers currently eligible for the vaccine feel comfortable receiving it. It is a heterogeneous group that includes people with different degrees of health literacy: certified nursing assistants, people who clean hospitals and provide food services, and help with home health, for example.

Unger says many of them are trying to decide if they want to be vaccinated and need more help answering their questions.

“What are we doing as a community and a state to make sure they have the answers they need to feel safe?” Unger said.

Unger also believes that the state should do a better job of reassuring the public that there is a plan to get everyone the vaccine – it’s just going to take time.

“The scarcity of a pandemic is very dangerous,” she said. ” Everyone is now trying to figure out how to feel safe and secure for their families, and I think the role for the government is to be able to communicate that we are going there, and there is hope. ‘