Earlier this week, the US Energy Information Agency (EIA) released figures on the new generating capacity that is expected to start operating in the course of 2021. While the plans may change, of course, the hope that the network with its new additions will look radically different from just five years ago. It contains the details of where a new nuclear power plant might start, although it will be dwarfed by the capacity of new batteries. But the big picture is that even if the batteries are ignored, about 80 percent of the planned addition to capacity will be released from emissions.

New nukes?

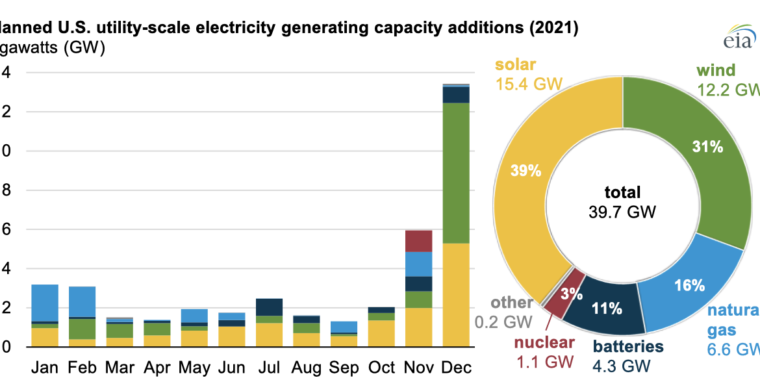

The EIA’s accounting shows that just under 40 Gigawatt of capacity will be put on the grid during 2021, but there are a number of caveats to this. In the first place is the inclusion of batteries, which make up more than 10 percent of the figure (4.3GW). While batteries may look such as short-term generating capacity from the perspective of “can it put power on the network?”, it is obviously not a net power source. Usually they are used to alleviate short-term fluctuations in demand or supply rather than a steady source of power.

Given the scarcity of mains batteries even a few years ago, 4.3GW of it is striking.

Another peculiarity is a matter of timing. Last year, Virginia’s Dominion Energy launched two offshore wind turbines as part of a pilot project that will give direction to the much larger Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind, which will reach 2.6GW when completed in 2024. But these turbines have not formally entered commercial services until this year, so they are 1.2 MW up to the 2021 figure.

Another case where the figures ultimately do not correspond to reality is the addition of 1.1GW of nuclear power in the form of a new reactor at the Vogtle site in Georgia. The construction of this plant and its twins consistently ran late and too little budget. If truly completed, it will be the first new core capacity to be added to the U.S. network in a few years, and the closure of some smaller plants in recent years will be partially offset.

But the big story in 2021 is the shift of fossil fuels. Despite the Trump administration’s efforts to tilt the playing field in favor of coal, no new coal capacity will be added in 2021. Given the recent closure of several major plants, it is a guarantee that the rapid decline in U.S. coal use is set to continue.

Until very recently, coal was largely displaced by natural gas. But in recent years, the prices of wind power have dropped to the point that a well-located wind farm in the US could supply power at a lower price than the cost of buying fuel for an existing natural gas plant. And the solar photovoltaics actually undermined wind power. But the market did not immediately respond to this new reality, and in recent years, natural gas has dominated the capacity added by the U.S. network.

Economy kicks in

The market is now responding clearly. Below 20 percent of the capacity added in 2021 will be natural gas (6.6GW), even if you do not disregard the added battery capacity. That is down from 34 percent just two years ago, and more than 60 percent three years ago. new additives are highly concentrated in areas where a lot of natural gas is produced: southern Texas and near the Ohio / Pennsylvania / West Virginia borders.

Instead, wind and solar power dominated, with 12.2GW of new wind capacity and 15.4GW of solar power. This is particularly striking as tax credits for renewable energy would be phased out in 2020, leading to many projects being implemented late in the year. (These credits were eventually extended in a recent budget bill.) Normally, the EIA predicts that this type of expiration could drain the pipeline of new projects, leading to a temporary decline. There is absolutely no indication that this happened in 2021.

These values especially do not include solar power, which is expected to add another 3GW to 4GW of capacity in 2021.

As in the past, Texas is one of the major sites for new wind construction, bringing together the northern neighbor of Oklahoma. Planned additions include a wind farm that is just a little less than a GigaWatt. Texas also dominates solar plants, with more than a quarter of the expected new capacity. Nevada and California will also install about 10 percent each, but they are closely followed by North Carolina, which is part of a growing trend of solar power plants in the U.S. southeast.

The Biden administration expects to promote additional renewable energy projects as part of its pandemic recovery plan. While it is unlikely that they will come fast enough to change the 2021 numbers, it could cause the wind and sun to rise even further in 2022. There are also a number of very large (GW-plus) offshore wind projects being developed on the U.S. east coast. some of which may begin service in the next few years.