Thousands of people refuse or deny US service members the Covid-19 vaccine while frustrated commanders scramble to destroy Internet rumors and find the right pitch that will persuade troops to get the chance.

Some military units believe that as few as one-third agree with the vaccine. Military leaders looking for answers believe they have identified one potentially compelling person: a looming deployment. Navy sailors on ships en route to the sea last week, for example, chose to take the shot at rates ranging from more than 80% to 90%.

Air Force Deputy Chief of Staff Jeff Taliaferro, deputy director of the joint staff, told Congress on Wednesday that “very early data” indicates that only two-thirds of the service members who offered the vaccine accepted.

This is higher than the percentage for the general population, which according to a recent survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation is about 50%. But the significant number of forces that the vaccine decreases is particularly worrying, as troops now live, work and fight together in environments where social distance and wearing masks is sometimes difficult.

The army’s resistance also comes as troops deploy to fire shots at vaccination centers across the country and while leaders look to U.S. forces to set an example for the country.

“We are still struggling with the messages and how we are influencing people to opt for the vaccine,” said Brigadier General Edward Bailey, the Army Surgeon’s Command. He said only 30% in some units agreed to take the vaccine, while others are between 50% and 70%. Power Command oversees important army units, comprising about 750,000 soldiers from the army, the reserve and the national guard at 15 bases.

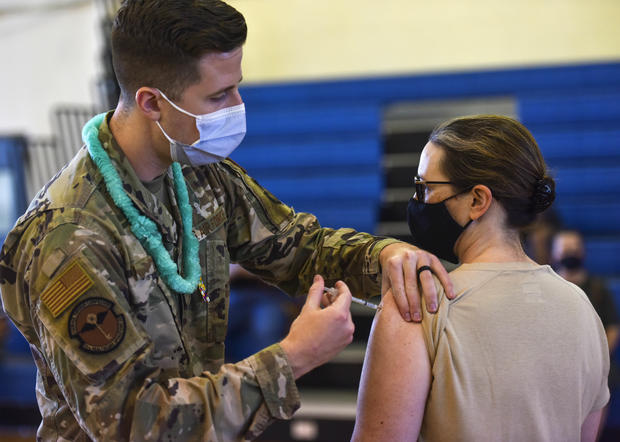

US Air Force Technology. Sgt. Anthony Nelson Jr./ Department of Defense via AP

In Fort Bragg, North Carolina, where thousands of troops are preparing for future deployment, the acceptance rate is about 60%, Bailey said. It’s not as high as we would hope for the frontline staff, ‘he said.

Bailey heard all the apologies.

“I think the most amusing one I heard was, ‘The military always tells me what to do, they gave me a choice, so I said no,'” he said.

Service leaders have been pushing hard for the vaccine. They held city halls, sent messages to power, disseminated scientific data, posted videos and even posted photos of leaders being vaccinated.

The Pentagon has been insisting for weeks that it does not know how many troops are taking the vaccine. On Wednesday, they provided little information about their early details.

However, individual military service officials said in interviews with The Associated Press that refusal rates vary widely, depending on age, service member unit, location, deployment status and other intangible things.

The variations make it harder for leaders to identify which arguments for the vaccine are most convincing. The Food and Drug Administration has allowed the use of the vaccine, so it is voluntary. But Department of Defense officials say they hope it can change soon.

“We can not make it mandatory yet,” said Vice Admiral Andrew Lewis, commander of the Navy’s Second Fleet, last week. “I can tell you that we’ll probably make it mandatory as soon as we can, just like with the flu vaccine.”

About 40 Marines recently gathered in a conference room in California for a medical staff briefing. One officer, who was not authorized to discuss private conversations in public and spoke on condition of anonymity, said marines are more comfortable asking questions about the vaccine in smaller groups.

The officer said one Marine, referring to a widespread and false conspiracy theory, said: “I heard this thing was actually a tracking device.” The medical staff, the officer said, quickly unleashed the theory and pointed to the Navy’s cell phone, noting that it was an effective tracker.

Other frequently asked questions revolved around possible side effects or health problems, including for pregnant women. Army, navy and air force officials say they hear much the same.

The Marine Corps is a relatively small service and troops are generally younger. Similar to the general population, younger service members are likely to decline or ask to wait. In many cases, according to military commanders, younger troops say they had the coronavirus or that they knew others who had it, and concluded that it was not bad.

“What they do not see is that 20-year-olds who became very ill were hospitalized or died, or that people look good, but then it appears that they have developed lung and heart disorders,” Bailey said.

One ray of hope was deployments.

Lewis, based in Norfolk, Virginia, said last week that sailors on the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower, who works in the Atlantic, agreed to get the shot at about 80%. Sailors on the USS Iwo Jima and Marines in the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit, which is also being deployed, had rates of more than 90%.

Bailey said the military sees opportunities to reduce the two-week quarantine period for units deployed to Europe if service members are largely vaccinated and the host country agrees. The U.S. military Europe can shorten the quarantine period to five days if 70% of the unit is vaccinated, and the incentive could work, he said.

Acceptance numbers are falling among those who do not deploy, military officials said.

Air Force Technology. Sgt. Anthony Nelson Jr./ Department of Defense

Army Chief of Staff James McConville used his own experience to encourage troops to be vaccinated. “When they asked me how it felt, I said it was much less painful than some of the meetings I go to in the Pentagon.”

Colonel Jody Dugai, commander of the Bayne-Jones Community Hospital in Fort Polk, Louisiana, said that so far group-level conversations with eight to ten peers have been successful, and that obtaining more information is helping.

At the Joint Readiness Training Center in Fort Polk, Brigadier General David Doyle faces a double challenge. As a base commander, he must persuade the nearly 7,500 soldiers at the base to get the chance, and he must ensure that the thousands of troops driving in and out for training exercises are safe.

Doyle said the acceptance rate at his base is between 30% and 40%, and that it is mostly the younger troops that are declining.

“They tell me they do not have a high level of confidence in the vaccine because they believe it was done too quickly,” he said. Health officials have testified to the safety and efficacy of the vaccine.

Doyle said peers often seem to have more influence than leaders in persuading troops – a sentiment echoed by Bailey, the army surgeon.

“We’re trying to figure out who the influencers are,” Bailey said. “Is it a group leader or a sergeant in the army? I think it’s probably. Someone who is more of their age and talks to them more on a regular basis than the general officer who takes his picture and says: “I shot it.”