Out of a wealth of caution, U.S. officials on Tuesday recommended halting the use of Johnson & Johnson’s COVID-19 vaccine. Officials linked the vaccine to six peculiar diseases in which people develop life-threatening blood clots in combination with low levels of platelets, the self-fragments in blood that clot. One person died due to their condition and another in a critical condition.

It is unclear whether the vaccine caused the diseases. Even if this did happen, the diseases would be an extremely rare side effect. The six cases occurred among more than 6.8 million people in the U.S. who received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. This will create a side effect seen in less than one in every million. The risk of hospitalization and death due to COVID-19, against which the vaccine protects, easily exceeds this chance. The benefits of the vaccine undoubtedly outweigh the potential risks.

Still, with robust supplies of Moderna and Pfizer-BioNtech vaccine – not linked to these unusual cases – U.S. officials have followed the cautious way of interrupting Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine while further investigating cases and informing clinicians about how to see it and treat any other that may arise. The latter point is critical, because if doctors try to use standard blood clot treatments in these vaccine-bound cases, the consequences can be fatal.

The other critical aspect of this situation, of course, is that officials have already seen these unusual cases – linked to a similar COVID-19 vaccine developed by AstraZeneca and researchers at the University of Oxford. The AstraZeneca vaccine has not yet been approved for use in the US, but it has been approved in many other countries, including those in the European Union. Regulators in the EU and the UK have been investigating dozens of similar cases in recent weeks, with dangerous blood clots and low platelets. Some estimates have linked the reported case of one in every 100,000 people vaccinated.

Now try to connect all the dots and find answers. Experts note the most obvious connection: both vaccines use an adenovirus vector, a viral delivery system that is frequently used in the development of vaccines.

Currently, the adenovirus vector provides ‘the simplest explanation’ for the possible side effects, says viral immunologist Hildegund Ertl, who is developing adenovirus-based vaccines at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia. However, the link to blood clots surprised us all, she tells Ars. The situation has raised a number of questions – as well as doubts.

Vexing virus

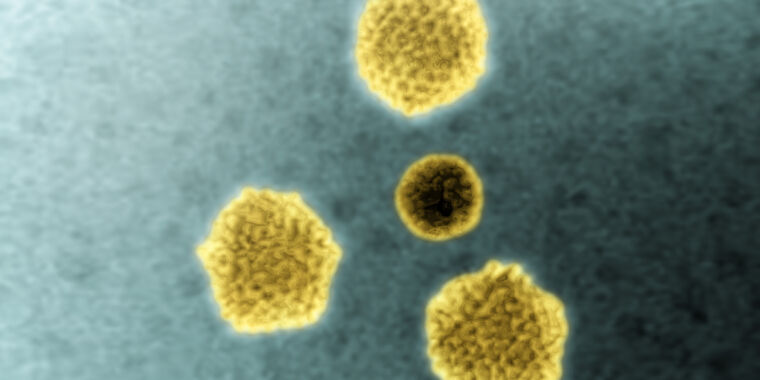

Adenoviruses are a large family of many common viruses that cause various infections in humans, from mild colds and flu-like illnesses to pink eye, pneumonia and gastroenteritis. In addition to humans, they can infect a variety of animals, including pigs, cows and chimpanzees. Researchers have been working with adenoviruses for decades. The Johnson & Johnson vaccine uses the adenovirus (Ad26), first identified in 1961 by children’s anal swabs in Washington, DC. The AstraZeneca vaccine is based on an adenovirus circulating in chimpanzees (ChAdOx1).

Over the years, researchers have considered adenoviruses to be useful delivery systems for vaccines and gene therapies. To begin with, it is easy to breed in large quantities in laboratory conditions. When designed for vaccines, it can elicit strong immune responses in humans against germs we want to fight. And they have appeared relatively safe in humans, especially since they are often adapted so that they cannot replicate in our cells.

But adenoviruses have had a difficult past. Researchers abandoned their use in gene therapy in 1999 only after the tragic death of 18-year-old Jesse Gelsinger. A team of researchers at the University of Pennsylvania has hoped to cure the teen’s rare metabolic disease by correcting an underlying genetic mutation with a new code – which is delivered in trillions of adenovirus vectors. The researchers use human adenovirus 5 (Ad5), which usually causes only mild colds. In early tests, the therapy caused only mild side effects and flu-like symptoms in animals and a human patient, The New York Times reported at the time. But in Gelsinger, the massive dose of viral vectors elicited a deadly immune response.

Researchers have contracted adenoviruses for the development of vaccines, where strong immune responses can be a plus rather than a danger. Adenoviruses, programmed as vaccine vectors, deliver important fragments of genetic code of dangerous viruses, bacteria or parasites directly to human cells. From there, our cells translate the genetic code into proteins, recognize them as foreign, and use them to train our immune systems to search for and destroy everything that contains the same protein. In the case of COVID-19, adenovirus-based vaccines contain the genetic code for the SARS-CoV-2 peak protein, which is the thorny protein that repels the virus’ particle. The spike protein is what SARS-CoV-2 uses to enter human cells, and it is an important target for powerful antibodies and other immune responses.

Shaky shots

Adenovirus-based vaccines have shown great promise over the years, but they have also had significant obstacles. Nearly a decade after Gelsinger’s death, researchers stopped a large-scale trial of an Ad5-based HIV vaccine after data showed the vaccine increased the risk of becoming infected with HIV in people who have already had immune responses to Ad5. With the sensational failure, many vaccine developers have moved away from Ad5 to other adenoviruses – people that tend to have less existing immunity, such as adenoviruses from chimpanzees.

Although researchers have developed adenovirus-based vaccines against a range of diseases – malaria, HIV, Zika, RSV (respiratory synthesis virus) and more – few have crossed the finish line and put them to use. One of the most successful is an Ad26-based Ebola vaccine made by Johnson & Johnson, which received regulatory approval in Europe last year. The approval boosted hopes for the COVID-19 vaccine, which uses the same Ad26-based platform.

Early in the pandemic, adenovirus-based vaccines are often seen as precursors, especially those of AstraZeneca. Despite the checkered past of adenovirus vectors, the design of the vaccine was seen as a more established technology than the mRNA-based vaccines, which was completely unproven to the extraordinary success of COVID-19 vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech. Adenoviruses also have logistical advantages. It is relatively inexpensive, easy to make and easy to distribute. Unlike the mRNA vaccines, which require ultra-cold storage conditions, AstraZeneca’s vaccine can handle normal refrigerator temperatures, for example. Many experts and the World Health Organization have considered the vaccination of AstraZeneca as the world’s vaccine – a cheap, accessible vaccine that can be used in different countries and environments.

But while the mRNA vaccines were advancing in the pandemic, AstraZeneca seemed to be hiding from problem to problem. The vaccine’s problems reached a critical point last month when more than a dozen countries temporarily suspended its use amid concerns that it was causing extremely rare blood clots. On April 7, an investigation by the European Medicines Agency of the EU concluded that there was a strong link between the vaccine and peculiar diseases involving blood clots and low platelets. The agency determined that they should be listed as ‘very rare side effects’ of the vaccine, but still urged countries to proceed with the vaccination.

“The reported combination of blood clots and low platelets is very rare,” the agency noted. “The overall benefits of the vaccine to prevent COVID-19 outweigh the risks of side effects.”