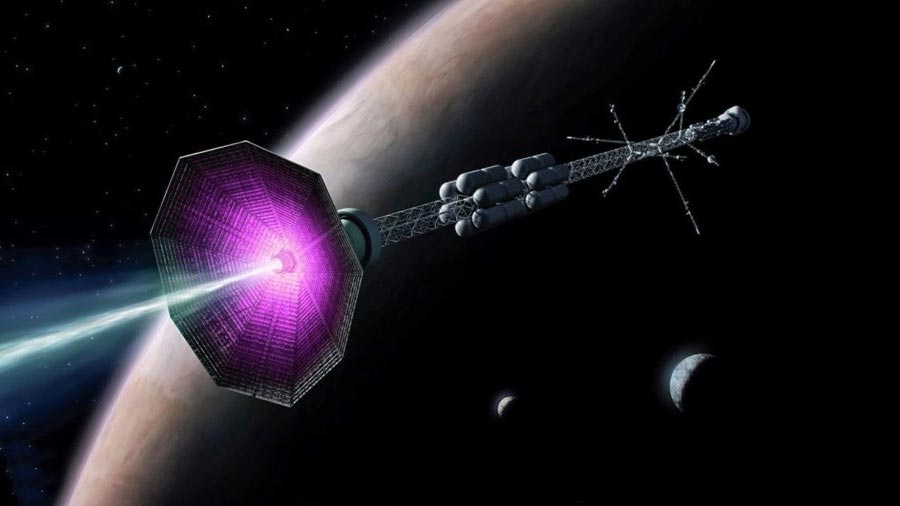

Fusion reactors are now considered to be the heat source that can bring rocket propellant to an extremely high temperature (and thus high velocity exhaust gases) or ultra-hot plasma to deliver thrust. Credit: ITER

A new kind of rocket propeller that humanity can imitate March and was further proposed by a physicist from the US Department of Energy (DOE)’s Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL).

The device will apply magnetic fields to cause plasma particles(link is out), electrically charged gas, also known as the fourth state of matter, to shoot out the back of a rocket and, due to the retention of momentum, propel the rig forward. Current space travel plasma drivers use electric fields to drive the particles.

The new concept will accelerate the particles using magnetic reconnection, a process found throughout the universe, including the surface of the sun, in which magnetic field lines converge, suddenly separate and then reassemble, producing much energy. Reconnection also takes place in donut-shaped fusion(link is out) devices known as tokamaks(link is out).

“I’ve been cooking this concept for a while,” said PPPL chief research physicist Fatima Ebrahimi, the inventor and author of an article.(link is out) what the idea in the Journal of Plasma Physics. ‘I had the idea in 2017 while sitting on a deck thinking about the similarities between a car’s exhaust and the high-speed exhaust particles created by PPPL’s National Spherical Torus Experiment (NSTX),’ the forerunner of the current flagship fusion facility in the laboratory. “During its action, these tokamak produce magnetic bubbles, called plasmids, that move about 20 kilometers per second, which to me looks a lot like shock.”

Fusion, the force that drives the sun and stars, combines light elements in the form of plasma – the hot, charged state of matter made up of free electrons and atomic nuclei that represent 99% of the visible universe – to generate massive amounts of energy wake. Scientists are trying to repeat the merger on Earth for a virtually inexhaustible power supply to generate electricity.

Current plasma propellants that use electric fields to drive the particles can only produce low specific impulse or speed. But computer simulations performed on PPPL computers and the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, a DOE office for science user facilities at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in Berkeley, California, have shown that the new plasma thruster concept can generate exhaust fumes. with speeds of hundreds of kilometers per second, 10 times faster than those of other drivers.

The faster velocity at the start of a spacecraft’s journey could bring the outer planets within reach of astronauts, Ebrahimi said. “Long-distance travel takes months or years because the specific impulse of chemical rocket engines is very low, so the vessel takes a while to locate quickly,” she said. “But if we make propellants based on magnetic reconnection, we can conceivably complete long-distance transmissions in a shorter period of time.”

There are three main differences between Ebrahimi’s screw concept and other devices. The first is that changing the strength of the magnetic fields can increase or decrease the amount of impact. “By using more electromagnets and more magnetic fields, you can turn a knob to refine the velocity,” Ebrahimi said.

Second, the new screw produces motion by ejecting both plasma particles and magnetic bubbles known as plasmoids. The plasmids give power to the propulsion, and no other thrust concept contains it.

Third, unlike current screw concepts that rely on electric fields, the magnetic fields in Ebrahimi’s concept allow the plasma in the screw to consist of heavy or light atoms. This flexibility allows scientists to adjust the amount of driving force for a specific mission. “While other propellants require heavy gas, made from atoms like xenon, you can use any type of gas you want in this concept,” Ebrahimi said. In some cases, scientists prefer light gases because the smaller atoms can move faster.

This concept broadens PPPL’s portfolio of space propulsion research. Other projects include the Hall Thruster Experiment started in 1999 by PPPL physicists Yevgeny Raitses and Nathaniel Fisch to investigate the use of plasma particles for moving spacecraft. Raitses and students are also investigating the use of small Hall propellers to give small satellites called CubeSats greater mobility as they orbit the earth.

Ebrahimi emphasized that her screw concept stems directly from her research on fusion energy. “This work is inspired by fusion work from the past, and this is the first time that plasmids and reconnection have been proposed for the propulsion of space,” Ebrahimi said. “The next step is to build a prototype!”

Reference: “An Alfvenic reconnecting plasmoid thruster” by Fatima Ebrahimi, 21 December 2020, Journal of Plasma Physics.

DOI: 10.1017 / S0022377820001476

Support for this research comes from the DOE Office of Science (Fusion Energy Sciences) and Laboratory Directed Research and Development (LDRD) funds made available by the Office of Science.