Scientists have for the first time successfully contained monkey embryos containing human cells – the latest milestone in a rapidly advancing field that has raised ethical questions.

In the work, published on April 15 in Cell1, the team injected monkey embryos with human stem cells and watched them evolve. They observed that human and apse cells divide and grow together in a dish, with at least 3 embryos surviving up to 19 days after fertilization. “The overall message is that each embryo contains human cells that multiply and differentiate to a different degree,” said Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, a developmental biologist at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California, and one of the researchers who led. the work.

Researchers hope that some human-animal hybrids – known as chimaeras – could provide better models for testing drugs and growing human organs for transplants. Members of this research team were the first to appear in 20192 that they could grow monkey embryos in a dish until 20 days after fertilization. In 2017, they reported a range of other hybrids: pig embryos grown with human cells, cow embryos grown with human cells, and rat embryos grown with mice3.

But the latest work has divided developmental biologists. Some question the need for such experiments with closely related primates – these animals are unlikely to be used as model animals such as mice and rodents. Non-human primates are protected by stricter research ethics rules than rodents, and they are concerned that such work is likely to provoke public outcry.

“There are many more meaningful experiments in this area of chimaeras than a source of organs and tissues,” says Alfonso Martinez Arias, a developmental biologist at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain. Experiments with livestock, such as pigs and cows, are “more promising and do not jeopardize ethical boundaries,” he says. “There is a whole field of organoids, which hopefully can do research on animals.”

Touching topic

Izpisua Belmonte says the team has no plans to implant hybrid embryos in monkeys. The aim is rather to better understand how cells of different species in the early growth phase communicate with each other in the embryo.

Efforts to cultivate human mouse hybrids are still tentative and the chimera must be more effective and healthier before it can be useful. Scientists suspect that such hybrids may have difficulty thriving because the two species are evolutionarily distant, allowing the cells to communicate in different ways. But observing cellular cross-talk in money-human embryo chimeras – involving two more closely related species – could suggest ways to improve the viability of future human-mouse models, says Izpisua Belmonte.

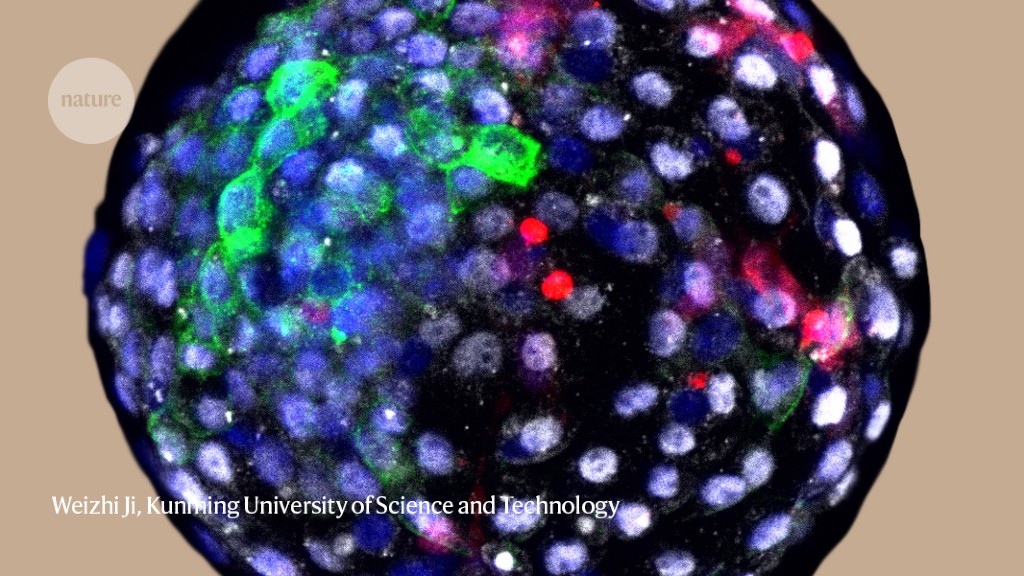

In the study, researchers fertilized eggs extracted from cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) and let them grow in culture. Six days after fertilization, the team injected 132 embryos with human elongated pluripotent stem cells, which can grow into a variety of cell types inside and outside an embryo. The embryos each developed unique combinations of human and monkey cells and deteriorated at different rates: 11 days after fertilization, 91 lived; it dropped on day 17 to 12 embryos and on day 19 to 3 embryos.

“This paper is a dramatic demonstration of the ability of human pluripotent stem cells to be incorporated into the embryos of cynomolgus monkeys when introduced into the monkey blastocysts,” said Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, a developmental biologist at the California Institute of Technology. in Pasadena.. She noted that this team, like others in the past, was unable to control which cells developed in which tissues – an important step to master before such models could be used.

Martinez Arias was not convinced by the results. “I expect better evidence,” especially of the later stages of development, he says. Those embryo numbers dropped rapidly as they approached day 15 of development, telling him ‘that things are very sick’.

The combination of human cells with closely related primate embryos raises questions about the status and identity of the resulting hybrids. “Some people may see that you are creating morally ambiguous entities there,” says Insoo Hyun, a bioethicist at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. He says the team has thoroughly followed the existing guidelines. “I think they looked after each other quite carefully to pay attention to regulations and ethical issues.”

Research restrictions

Meanwhile, international guidelines are catching up in the field – next month the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) is expected to publish revised guidelines for stem cell research. Hyun, who chairs an ISSCR committee discussing chimaeras, will address this to non-human primates and human chimaeras. The group’s guidelines currently prohibit researchers from mating chimeras between humans and animals. The group also recommends extra supervision when human cells can integrate with the developing central nervous system of an animal gas.

Many countries – including the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan – have at one time conducted limited research on chimeras involving human cells. Japan lifted its ban on experiments with animal embryos containing human cells in 2019 and began funding such work in that year.

In 2015, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced a moratorium on federal funding for studies in which human cells would be injected into animal embryos. In 2016, the funding agency proposed that the ban be lifted, but that research be limited to hybrids that arise after gastrulation, when the early nervous system begins to form. More than four years later, the funding ban still applies. A NIH spokesman said the agency was awaiting the May ISSCR update ‘to ensure our position reflects community input’, but did not provide a timeline for the agency’s rules to be released.