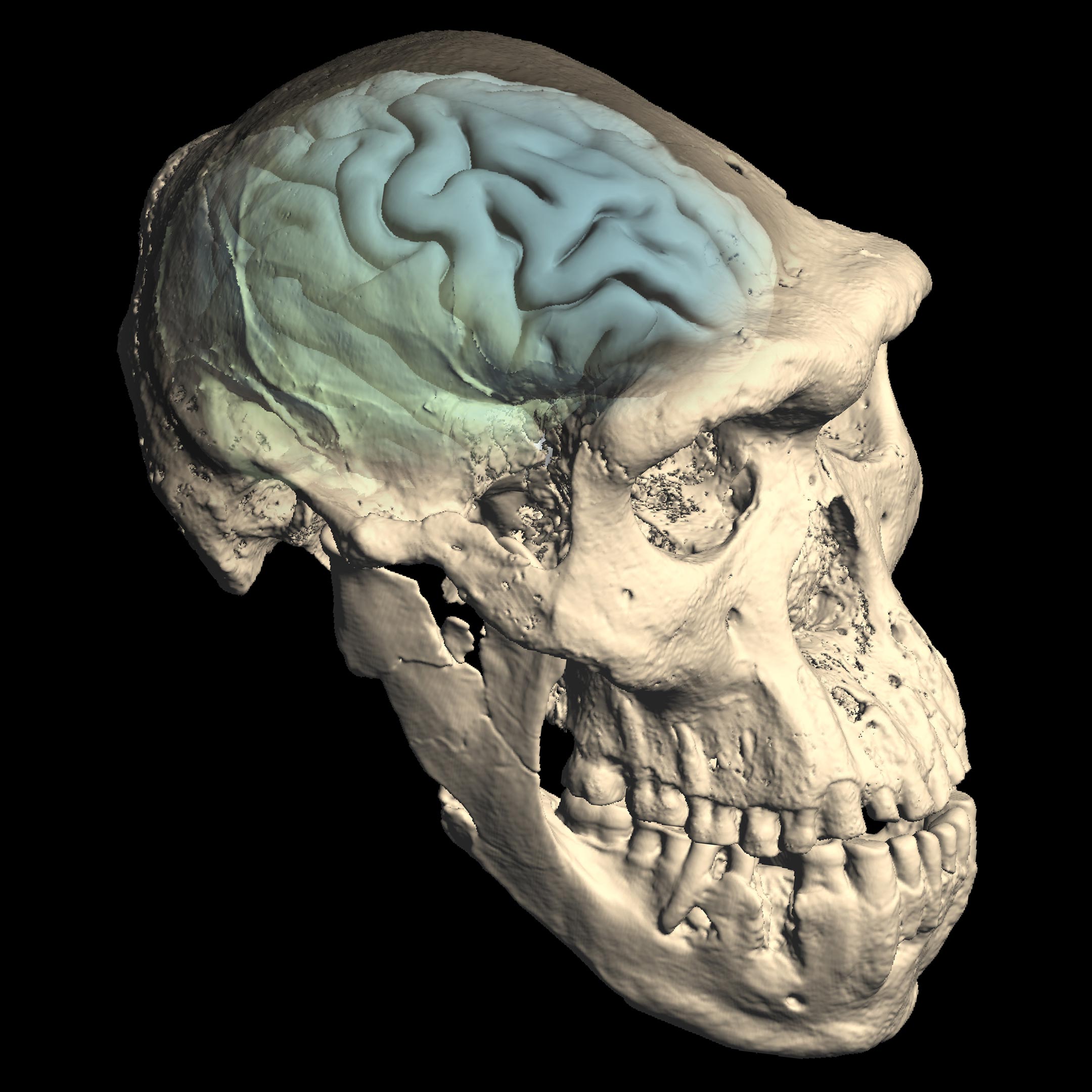

Skulls of early Homo from Georgia with a monkey-like brain (left) and from Indonesia with a human-like brain (right). Credit: Mr. Ponce de León and Ch. Zollikofer, UZH

The human brain as we know it today is relatively young. It developed about 1.7 million years ago when the culture of stone tools in Africa became increasingly complex. Some time later, the new Homo populations spread to Southeast Asia, researchers from the University of Zurich have now shown using computed tomography analyzes of fossilized skulls.

Modern humans are fundamentally different from our closest relatives, the great apes: we live on the ground, walk on two legs and have much larger brains. The first population of the genus Homo originated in Africa about 2.5 million years ago. They were already walking upright, but their brains were only half as big as today’s people. These earliest homopopulations in Africa had primitive ape-like brains – just like their extinct ancestors, the australopithecines. So, when and where did the typical human brain develop?

CT comparisons of skulls reveal modern brain structures

An international team led by Christoph Zollikofer and Marcia Ponce de León from the Department of Anthropology at the University of Zurich (UZH) has now managed to answer these questions. “Our analyzes suggest that modern human brain structures originated in African homopopulations only 1.5 to 1.7 million years ago,” says Zollikofer. The researchers used computed tomography to examine the skulls of Homo fossils that lived in Africa and Asia 1 to 2 million years ago. They then compare the fossil data with reference data of great apes and humans.

Skull of the early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia, which shows the internal structure of the brain matter and deduced the brain morphology. This was revealed by computed tomography and virtual reconstruction. Credit: Mr. Ponce de León and Ch. Zollikofer, UZH

Apart from the size, the human brain differs from the great apes, especially in the location and organization of individual brain regions. “The characteristics that are typical of man are mainly the regions in the frontal lobe that are responsible for the planning and execution of complex thought patterns and ultimately also for language,” notes the first author Marcia Ponce de León. As these areas are significantly larger in the human brain, the adjacent brain regions have moved further back.

Typical human brain spread rapidly from Africa to Asia

The first Homo population outside Africa – in Dmanisi in present-day Georgia – had brains that were just as primitive as their family members in Africa. It therefore follows that the brains of early humans only became particularly large or particularly modern about 1.7 million years ago. However, these early people were able to make numerous tools, adapt to the new environmental conditions in Eurasia, develop food resources and provide care for group members in need.

Dmanisi skull, mounted for synchrotron tomography at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in France. Credit: Paul Tafforeau, ESRF

During this period, the cultures in Africa became more complex and diverse, as evidenced by the discovery of different types of stone tools. The researchers think that biological and cultural evolution are likely to be interdependent. “It is likely that the earliest forms of human language also developed during this period,” says anthropologist Ponce de León. Fossils found on Java provide evidence that the new population was extremely successful: shortly after their first appearance in Africa, they had already spread to Southeast Asia.

Brain impressions in fossil skulls reveal the evolution of humans

Previous theories have little support for them due to the lack of reliable data. ‘The problem is that the brains of our ancestors were not preserved as fossils. Their brain structures can only be deduced from impressions left by the folds and furrows on the inner surfaces of fossil skulls, ”says study leader Zollikofer. Because these prints differ greatly from individual to individual, it has not been possible until now to determine whether a particular Homo fossil has a more ape-like or more human brain. Using computed tomography analyzes of a series of fossil skulls, the researchers were able to close the gap for the first time.

Reference: “The primitive brain of early Homo”By Marcia S. Ponce de León, Thibault Bienvenu, Assaf Marom, Silvano Engel, Paul Tafforeau, José Luis Alatorre Warren, David Lordkipanidze, Iwan Kurniawan, Delta Bayu Murti, Rusyad Adi Suriyanto, Toetik Koesbardiati and Christoph PE Zollikofer, 9 April 2021 , Science.

DOI: 10.1126 / science.aaz0032