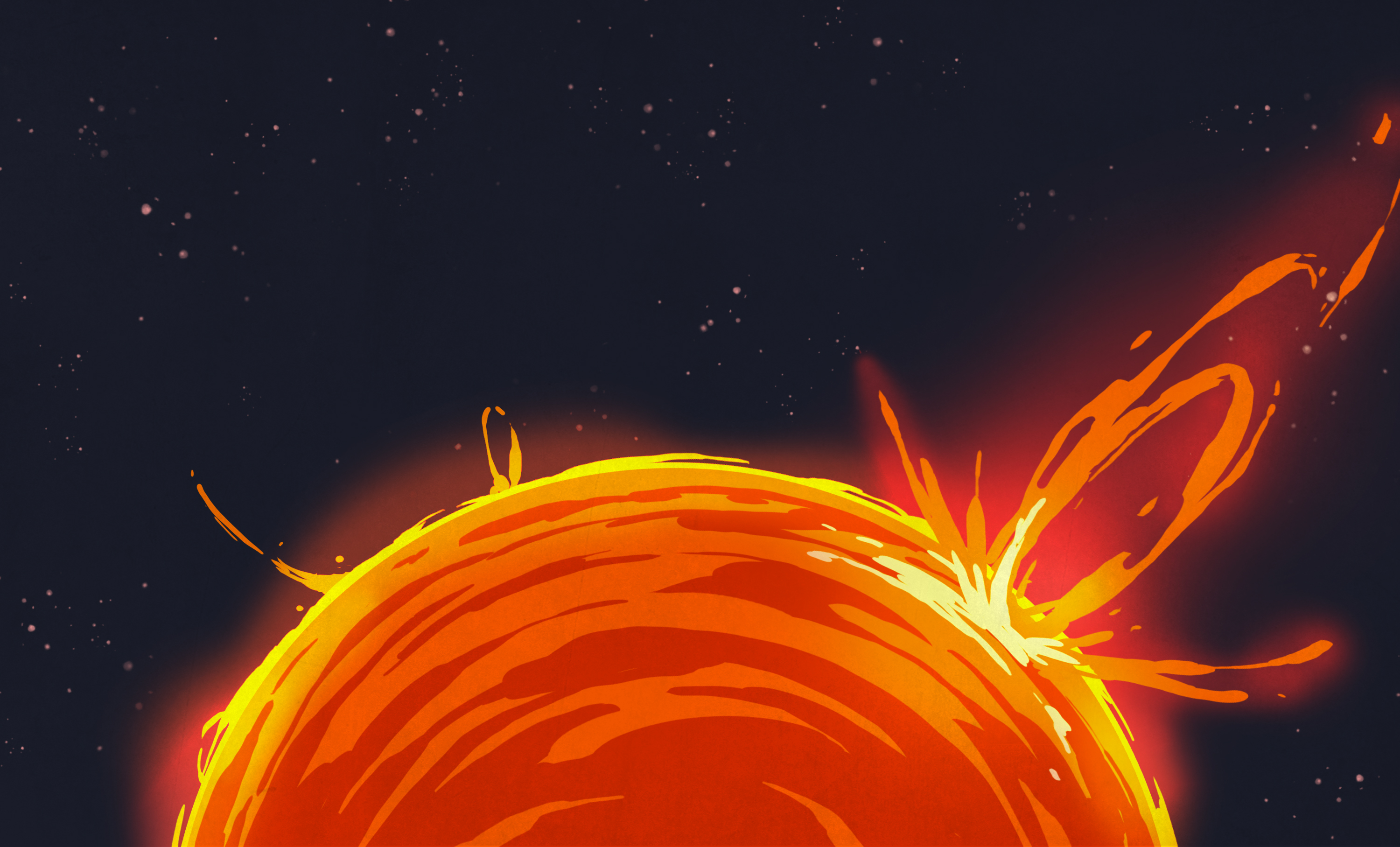

On November 8, 2020, the sun exploded. Well, it’s a bit dramatic (it explodes a lot) – but a particularly large sunspot called AR2781 produced a C5 class sunburn, which is a medium explosion even for the sun. Torches range from A, B, C, M and X with a scale of zero to nine in each category (or even higher for giant X torches). So a C5 is about a dead end of the scale. You may not have noticed it, but if you lived in Australia or the Indian Ocean and used your radio frequencies below 10 MHz, you would have noticed, as the torch caused a 20 minute radio blackout at the frequencies.

According to NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center, the sunspot has the energy to produce M-class torches that are of greater order. NOAA also has a scale for radio interference ranging from R1 (an M1 torch) to R5 (an X20 torch). The sunspot in question is currently facing the earth, so any new torches will cause more problems. This prompted us to ask ourselves: What if there was a major radio disturbance?

It happens more often than you might think. In October, AR2775 ignited two C-torches and although the plasma of the torch did not hit the earth, UV radiation caused a brief radio interruption over South America. The X-rays and UV radiation move at the same speed as light, and by the time we see a torch, it’s too late to do anything about it, even if we could do it.

The effects are mostly related to the propagation of radio waves via the ionosphere. Who would care in the 1700s? But in the mid-20th century, many things relied on this feature of high-frequency radio waves. Today, it may not matter nearly as much.

If you own a shortwave radio, you may have noticed that not much was broadcast after decades ago. Broadcasters who want to reach an international audience use the internet to do so now, unless they target a part of the world where internet is scarce or limited. Even the AM radio group is not the mainstay it was. Many people listen to FM (which propagates differently), satellite radio, or they stream audio from the internet. Of course it uses radio, but not propagation by ionosphere.

Intercontinental transport

Perhaps the biggest commercial users of the radio bands are now aircraft and ships at sea, but even then many of these uses now use satellites and much higher frequencies. Ham radio operators are of course still there, just like standard time and frequency stations like WWV. Although there have been radio frequency navigation systems like LORAN and Gee, almost all of them are in favor of GPS.

Indeed, major events – the so-called Carrington events – can directly affect many electronics. The insurance industry estimates that this could amount to up to $ 2.6 billion in damages. Worried? Maybe keep an eye on the space weather channel. If you’re interested in what the United States government would do if we had an opportunity at Carrington level again, they wrote it all out. Honestly, however, it seems that the plan makes better predictions and develops new technology. FEMA has an information graph that claims that a solar flare can affect your toilet, although it looks like it will take some time before that happens. It’s a little more interesting to read their excellent but not yet released memo on the subject. The maps on pages 16 and 17, which indicate where the power grid is vulnerable to geomagnetic storms, are particularly interesting.