The COVID-19 winter strike has ravaged much of Los Angeles County, and the number of deaths and deaths has skyrocketed for weeks.

But in some neighborhoods, the wrath of the pandemic was barely felt.

In West Hollywood, Malibu and Playa del Rey, infection rates have actually dropped or increased much less than elsewhere, according to a Times data analysis of more than 300 neighborhoods and cities in the country.

The relative happiness of those communities can be explained by a few obvious demographic factors, such as the low housing density of Malibu and the large population of singles in West Hollywood who can work from home.

But residents and city officials also point to other factors that they say helped keep the pandemic under control: sea breezes, easy access to open space to practice, a strong culture of mask compliance and, most importantly, limited contact. with other people.

“I’m well aware that I’m in the minority,” said Shayna Moon, a project manager for a technology company that works at home in Playa del Rey, where the rate fell during the boom. “As few people were protected as people my age and my income group and education were.”

The data analysis highlights the debilitating inequalities that the pandemic in LA County and beyond revealed.

Some areas – the eastern side, the eastern San Fernando Valley, southern LA and the southeastern part of the country – have been devastated by the coronavirus. Many of these are low-income communities with a large number of residents who are essential workers, risking their lives at supermarkets, manufacturing companies and other businesses. It is very likely that they will live in overcrowded conditions, which could cause the coronavirus to come out of work and spread it among the household.

Heavily affected areas do not have the assets – large recreational space and a population with the economic means to stay at home, deliver goods and work remotely – of prosperous communities that have performed better. It was not just living in sprawling single-family homes, rather than denser apartments that made the difference, but additional economic and lifestyle factors.

Taken as a whole, these factors outline a story of two rises that show that the luxury of location and privilege play an important role in the ability to avoid the coronavirus.

This story, which examined weekly fall rates between November 15 and January 15, deals with some of the places where the holiday took off.

Malibu

Masked visitors to Malibu Pier, with shops, fishing and restaurants open for dining.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

In the courtyard of a Malibu shopping square, Renee Henn, 27, sat on a bench in the sun last week while people drank around drinking coffee, chatting at tables at a physical distance during lunch and in a Pilates class. studio drop by.

Henn, who lives in a house near the beach with her father and his girlfriend, was able to work remotely for a local technology company during the pandemic. She said lack of density, lifestyle factors and even the Malibu climate could help explain the area’s relatively tame COVID-19 numbers.

“We were healed near the water and the sea air,” she said. “Everyone is outside all the time.”

While the coronavirus case in LA County exploded by 450% during the boom, the case for the city of Malibu only doubled. This puts it at the top of the list of communities least affected by the boom.

Expensive real estate may have helped isolate Malibu. According to the census data, the average home value in the coastal community is $ 2 million, and many of the essential workers at restaurants, grocery stores and other businesses in its compact commercial district live outside the area.

The affluent residents of the city were able to start work quickly after the pandemic began to work, and most services and meetings in the town hall immediately switched to online.

“A lot of people in Malibu were able to adapt to work from home,” said City Mayor Mikke Pierson, “and I think it made a big difference compared to all the people who had to go 9-to-5. work that required them to be among other people. ”

Pierson noted that Malibu did not have nursing homes or long-term care facilities (although there were attempts to establish some), which was central to the outbreak of the virus.

But as a tourist destination, Malibu carries some risks. Malibu sees up to 15 million visitors a year as a “concern” during the pandemic as a crowd on beaches and roads, city spokesman Matt Myerhoff said.

To encourage healthy behavior, the city council adopted a ordinance in November requiring the use of masks. It is enforced with a $ 50 fine that can be avoided if the offender complies immediately. The city has also placed digital directions along highways to encourage the use of face masks in public.

‘The city uses all its communication channels to repeat and strengthen the country [Los Angeles County] safety recommendations for public health officials [and] health orders, ”Myerhoff said.

In addition, the area has a lot of open space. Julia Bagnoli, 36, lives in an ‘air stream in the forest’, she said in the hilly area of Topanga just east of Malibu. She has a number of jobs – including counseling for alcohol treatment and yoga instruction at a primary school – but her primary occupation is Vedic astrology, which she has been able to practice remotely throughout the pandemic.

Compared to her woody home, ‘the city is just more crowded’, she said while playing with her puppy Usha on a shopping mall on the Pacific Coast Highway. She noted that there are only about 10,000 people in Topanga and less than 14,000 in Malibu. ‘There are about 14,000 people in a four-block radius in Hollywood. We are just more spread out. ”

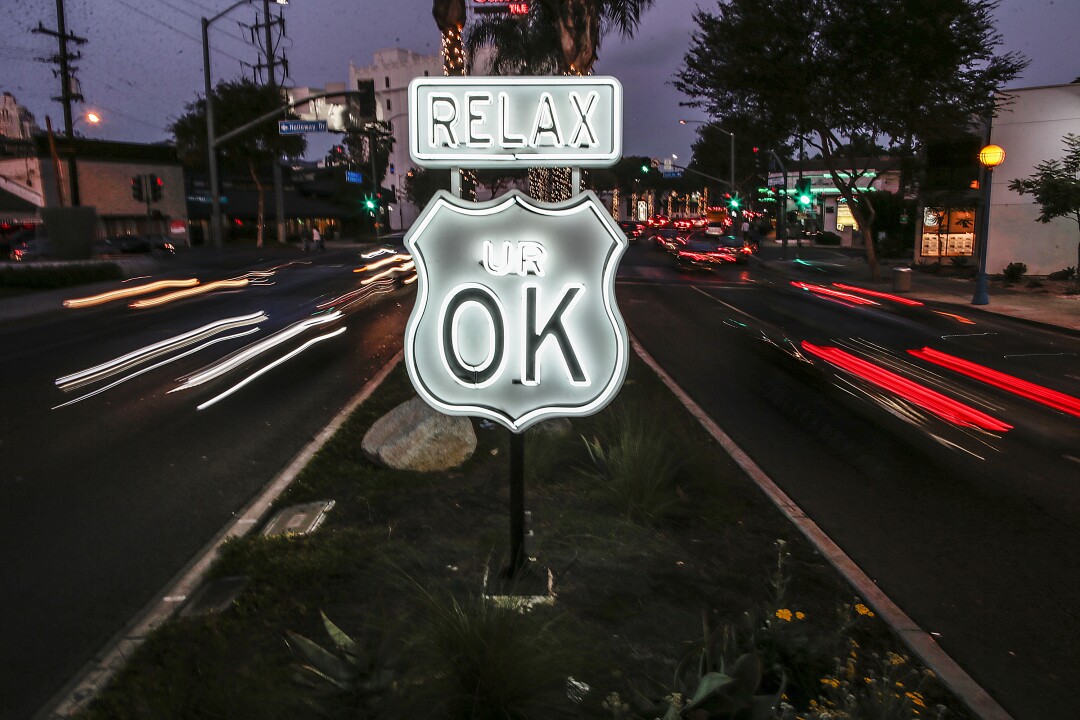

West Hollywood

Cars stream through the intersection of La Cienega Boulevard and Holloway Drive in West Hollywood.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

West Hollywood seems in some ways to be an excellent candidate as a superspreader environment. The city stops 36,000 people in less than 2 square kilometers.

But while other densely populated areas in the country, including parts of southern LA and the San Gabriel Valley, saw the case of coronavirus cases skyrocket by more than 1,000% during the boom, West Hollywood saw the cases with only 46% climb.

The main difference: household size. West Hollywood is, according to urban data, a place where many residents live alone. And many of the residents of the area were able to work from home throughout the pandemic.

These options are off the table for many of the vital workers and people who depend on multigenerational housing in parts of LA that have been hit hard by the boom.

Dex Thompson, a 33-year-old actor, said he is the sole occupant of his home near the busy intersection of Fairfax Avenue and Santa Monica Boulevard and has been going on “Zoom auditions” since the start of the pandemic. Even the decision to audition was deliberate, he said.

“Here’s a little narcissism,” Thompson said of West Hollywood as he snacked on sushi and some juice outside Whole Foods. “Everyone feels a little important, like, ‘I’m about to be someone, and you are not, so am I going to risk my life for you or for this occasion?'”

A sign of encouragement shines the median of Santa Monica Boulevard in West Hollywood.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

The luxury – of housing, jobs and choices – was in many ways a determining factor in the midst of the pandemic.

Lisa Cera, a stylist, said she and her business partner managed to keep their business going by working out of her apartment.

Like Thompson, she’s the only occupant of her home, which is around the corner from West Hollywood’s commercial corridor. She has three interns, two of whom work remotely – and are tested for the coronavirus when she has to walk on a movie set.

Although Cera has friends on the East Coast who contracted COVID-19, she said she does not know anyone in West Hollywood who had it.

Staying fit may have helped her and others around her stay healthy during the pandemic, she said. She walks almost every day in Runyon Canyon and is careful to tighten her mask when someone comes near her on the popular trail.

Although ocean breezes and gourmet juices may seem like less than quantifiable factors, there is one issue that needs to be related to the link between the health and avoidance of COVID-19.

Lifelong, systemic lack of access to primary health care and nutrition, as well as environmental factors such as pollution, may contribute to a greater likelihood of disease and death due to the virus, according to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Many of these factors have long plagued the poorer, denser and more diverse parts of the country worst hit during the boom.

West Hollywood’s network of social programs may have made a difference, too. City spokeswoman Lisa Belsanti said the city provided vulnerable residents with free groceries and meals, provided assistance to tenants and small businesses, and developed advanced technological outreach and communication efforts.

In addition, West Hollywood, like Malibu, has enacted a regulation requiring the use of masks in public.

Some residents said the combination of factors works.

“We are a small town,” said Douglas, 49, a real estate developer who did not want to be named. “West Hollywood is good at communicating policy and getting the information out.”

Playa del Rey

In Playa del Rey, a wealthy beach neighborhood near Los Angeles International Airport, the pandemic has barely registered.

In fact, infection rates dropped by 25% over the two-month period identified by The Times.

The area in the heart of Silicon Beach does not have the spaciousness of Malibu, but it seems to have demographic advantages. The coastal community is largely residential, with a mix of single-family homes and apartments, and it has less crowded households than most neighborhoods and cities in the country, according to a Times review of data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

It is also one of the richest – and has a high percentage of servants, which means that many are likely to have the benefit of working from home.

Moon, the project manager and a Midwest transplant in the neighborhood, was careful to adhere to public health guidelines and expressed gratitude that her employer had allowed her to work from home since April.

Moon said she does not walk outside her apartment without a mask – and rarely ventures beyond groceries and drugstores.

‘I take very little risk every day. “I was basically isolated from it because of the demographics I was in,” she said.

Perry Chung walks through the popular Playa del Rey shopping center with a coffee from Playa Provisions.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

Public health precautions – such as home orders and alternating bans on indoor and outdoor dining – have taken their toll in the area.

At Playa Provisions, a well-known eatery just off the beach, business is down 75%.

“We love that we are the right staple food and reliable place to come,” said Brooke Williamson, the co-owner and co-chef of the restaurant. “Every moment of this was so painful.”

She and her staff never relaxed their safety measures, even though the environment fared better than other parts of the country, she said.

‘I tried not to think that the area was not dangerous. I always treated my restaurant, my staff and family as if we were in the areas at greatest risk of trying to avoid being relaxed in any way. ”

While Williamson was chatting, more than a dozen people walked past her restaurant. Everyone wore masks.