Three hundred years ago, in front of envelopes, passwords and security codes, writers often struggled to keep thoughts, caring and dreams expressed in their letters.

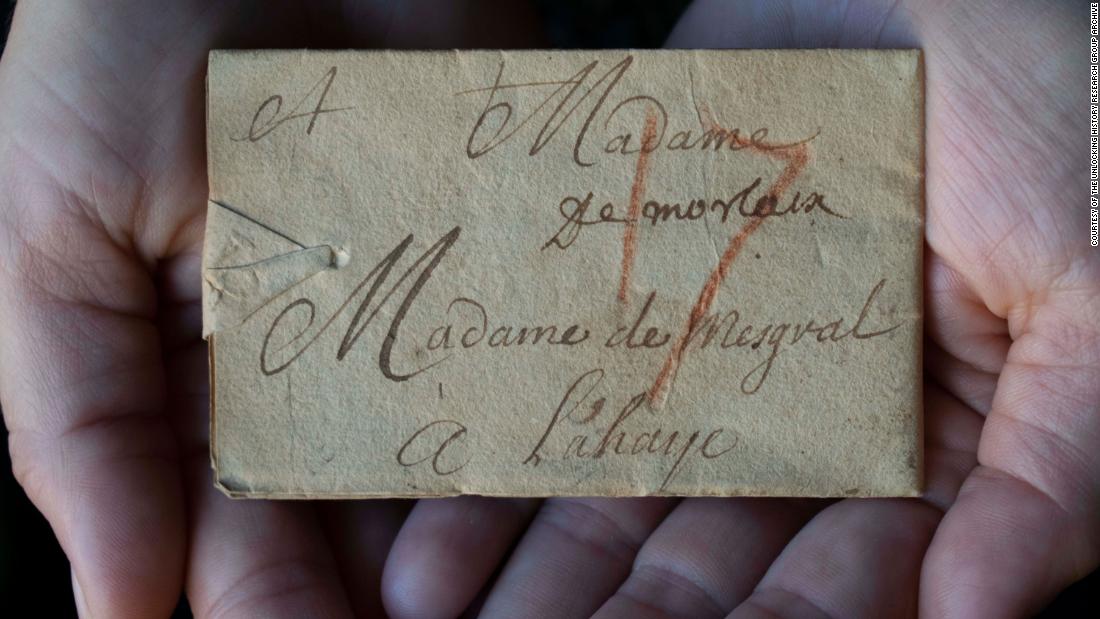

One popular way was to use a technique called letter locking – to fold a flat sheet of paper in an intricate way to become its own envelope. This security strategy was a challenge when 577 closed letters delivered to The Hague in the Netherlands between 1689 and 1706 were found in a trunk of uninitiated mail.

The letters have never reached their final recipients, and conservationists did not want to open and damage them. Instead, a team found a way to read one of the letters without breaking the seal or folding it open in any way. Using a highly sensitive X-ray scanner and computer algorithms, researchers virtually unfolded the unopened letter.

It is a computer-generated unfolding sequence of a sealed letter from 17th-century Europe. Virtual unfolding was used to read the contents of the letter without physically opening it. Credit: Thanks to the Unlocking History Research Group archive

“This algorithm takes us to the heart of a closed letter,” the research team said in a statement.

“Sometimes we resist the past investigation. We could have simply cut open these letters, but rather we took the time to study them for their hidden, secret and inaccessible properties. We have learned that letters can be much more revealing than they are. left unopened. ‘

The technique reveals the contents of a letter dated 31 July 1697. It contains a request from Jacques Sennacques to his cousin Pierre Le Pers, a French merchant in The Hague, for a certified copy of a death notice of Daniel Le Pers .

The details may seem prosaic, but the researchers said the letter provides a fascinating insight into the lives of ordinary people – a snapshot of the early modern world.

This 17th century tribe of non-delivery letters was bequeathed to the Dutch Post Museum in The Hague in 1926. A letter from this trunk was scanned by X-ray microtomography and virtually unfolded to reveal its contents for the first time in centuries. Credit: Thanks to the Unlocking History Research Group archive

In addition to the unopened letters, it contains 2,571 opened letters and fragments that for some reason never reached their destination.

At the time, there was no such thing as a postage stamp, and recipients, not senders, were responsible for the postage and delivery costs. If the recipient died or the letter was rejected, no fees could be collected and the letters were not delivered.

A new way to extract historical documents

The X-ray scanners were originally designed to map the mineral content of the teeth and have been used in dental research until now.

“We were able to use our scanners to use X-ray history,” author David Mills, a researcher at Queen Mary University of London, said in a statement.

“The scanning technology is similar to medical CT scanners, but uses much more intensive X-rays that allow us to see the small traces of metal in the ink used to write these letters. The rest of the team was then able to do our scan. images and turn them into letters that they could open and read for the first time in more than 300 years. ‘

The letter contains a message from Jacques Sennacques on 31 July 1697 to his cousin Pierre Le Pers, a French merchant. A watermark in the middle is also visible with an image of a bird. Credit: Thanks to the Unlocking History Research Group archive

The study said the new technique has the potential to unlock new historical evidence from the Brienne trunk and other collections of unopened letters and documents.

“The use of virtual unfolding to read an intimate story that has never seen the light of day – and that the recipient has never reached, is extremely extraordinary,” the researchers said.

The research was published in the journal Nature Communications on Tuesday.