The future of cancer treatment could be accompanied by personalized vaccines designed to manage or even prevent relapses – at least as new research published on Thursday continues to expand. In a small clinical trial, high-risk melanoma patients who received such a vaccine could create a long-term, lasting immune response to their cancer, scientists said. They also survived four years after initial treatment, most of whom were actively disease-free.

Cancer vaccines have been a sought-after target by scientists for decades. There are two vaccines that can protect against viral diseases that increase the risk of certain cancers, HPV and hepatitis B. But developing a broad effective vaccine that can prevent cancer directly has been a more difficult task, thanks to the nature of Cancer. First, cancer cells are mutated versions of the cells found in our body, so our immune system cannot recognize them as easily as an enemy. And because each cancer is specific to each person, it is not that simple to create a vaccine that works for everyone.

In recent years, however, there have been advances in the development of cancer vaccines on a more personal level. Researchers have discovered that tumors carry proteins on the surface of their cells that are not found in normal cells, and may make them look different from our immune system. These proteins are called neoantigen. By creating vaccines that train the immune system to better recognize these neo-antigens, scientists can theorize, we can give our bodies a better chance of fighting a known cancer.

Scientists from the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Massachusetts and elsewhere are working on one of these vaccines (called NeoVax) for skin cancer melanoma as well as glioblastoma, the most common form of brain cancer and one that is very difficult to treat. While they have work showed that the vaccine is well tolerated and appears to elicit an immune response in patients, so far only short-term results are available. Their new paper, published in Nature Medicine, suggests that their vaccine also works over the long term.

‘These neoantigens are the result of mutations that occur in a specific tumor – it is something that is created on an individual level. “Our vaccines must therefore be tailored to a patient’s cancer,” author Patrick Ott said by telephone. “But what’s new is that we were able to identify these mutations much faster and in a more cost-effective way than before using genomics and sequencing.”

G / O Media can get a commission

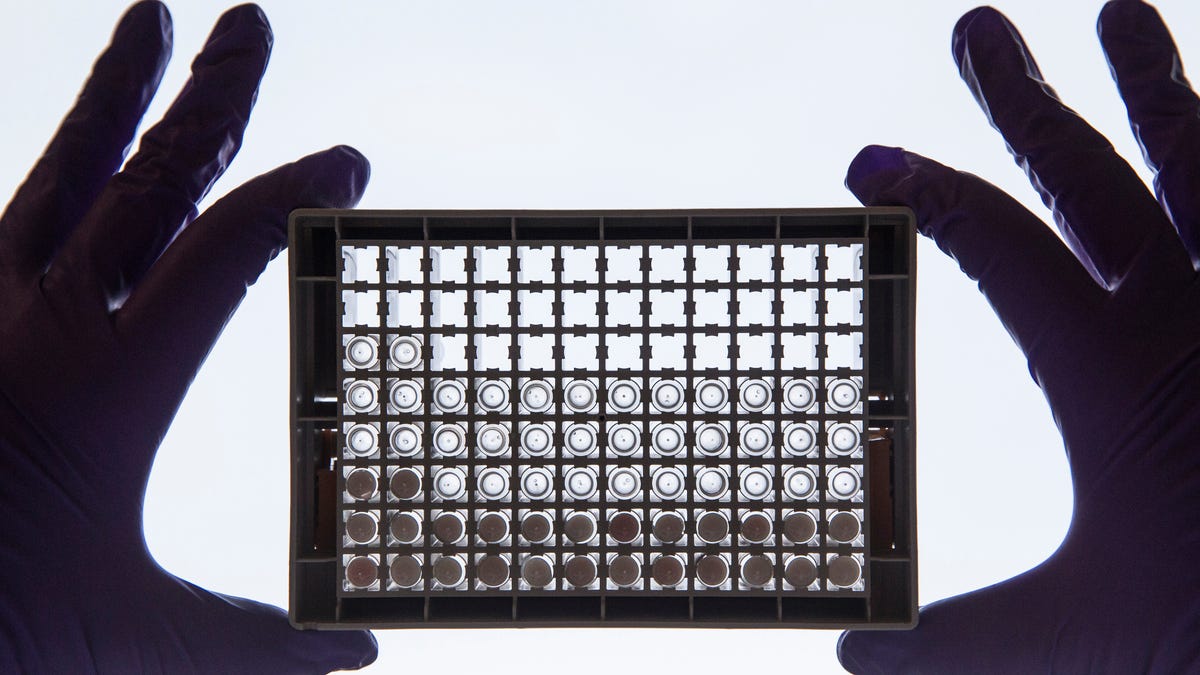

They gave NeoVax to eight patients who were considered at high risk for future, potentially fatal recurrences of advanced melanoma. Thereafter, they monitored their health for the next four years and took regular blood samples to study the body’s immune response to the cancer, especially tumor-specific T cells.

The vaccine was given to patients approximately 18 weeks after surgery to remove the tumor. Ott and his team found that volunteers continued to carry T cells that specifically related to the neo-antigens that their vaccine trained the immune system to remember. In some people, they have also seen T cells that recognize other neo-antigens specifically for their tumor. This is an indication that their immune systems are adapting to any persistent tumor cells in the body by creating even more weapons against them. All eight patients were still alive after nearly four years, and six appeared disease-free at the last check-in.

At present, it takes at most three months before a person’s diagnosis creates a personalized vaccine, before scientists like Ott. But it may be possible that these vaccines can be created in a much shorter time after a simple doctor visit. And while it may not be the ‘universal’ cancer vaccine we all hope for, Ott sees no reason why these vaccines could not ultimately be made to prevent relapses of any form of cancer.

The vaccines can probably be combined with other treatments. Two patients in the study with cancer spread elsewhere were given immune system inhibitors, medicines that allow the immune system to better target tumor cells. In these patients, the group found evidence that tumor-specific T cells found their way to the metastatic tumors.

In the future, Ott and his team hope to refine their vaccine technology to create even more powerful immune responses that, in combination with drugs such as immune-control inhibitors, can manage advanced cancer cases. They are also now testing their vaccine with other cancers, while continuing to monitor their existing patients.