How exactly is it perhaps what happened hundreds of millions of years ago is, however, long an evolutionary mystery that has astonished scientists.

U.S. scientists say they may have stumbled upon a possible answer.

By adapting a single gene, researchers at Harvard University and Boston Children’s Hospital designed zebrafish that showed the onset of attachments indefinitely.

To answer how animals made the transition from sea to land, scientists have traditionally looked at the fossil record. But in the last 30 years, scientists have been searching for changes in genes that could explain the shift from fin to modern limb.

“Prior to this discovery, the assumption was that the fin-to-limb transition involved multiple changes to a multitude of genes,” he noted via email.

“Of course, this transformation was still a very gradual and complicated process, but our mutants show that it may also have involved rapid leaps, and that developing animals are able to easily take on new bones.”

Inborn ability

While previous research has identified genes needed to make fin and limb bones, no one has previously found a genetic change that causes a fin to shift to a more limbic pattern, Hawkins explained by email.

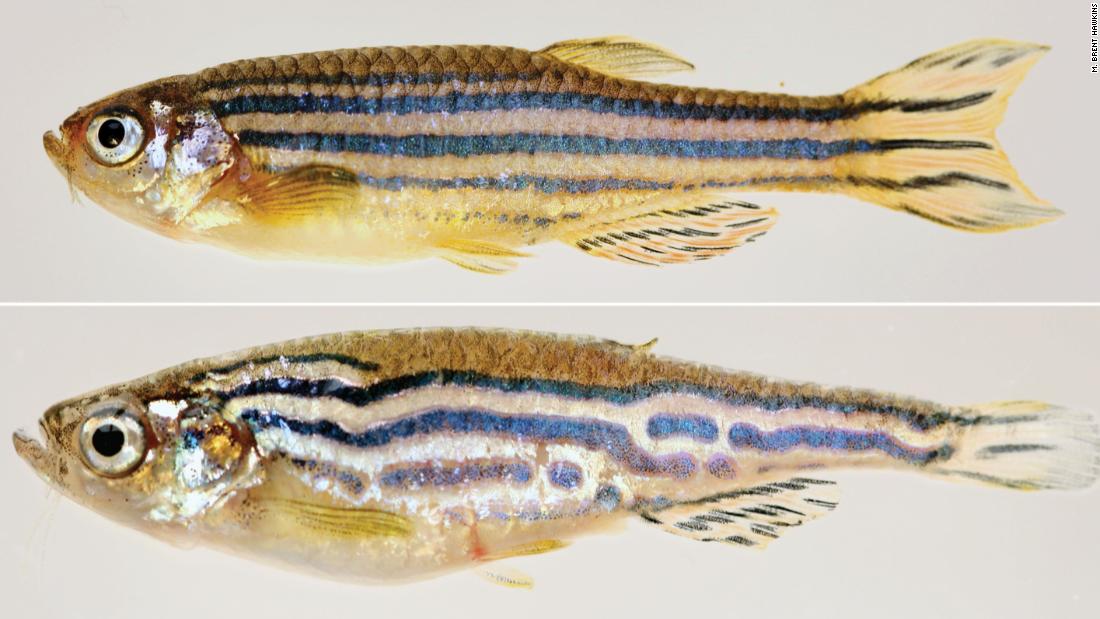

The mutation that the researchers found causes a change in the pectoral fin bones of the zebrafish, which sticks a bit to the fish shoulder joint as the human arm attaches to the shoulder.

A new set of long legs – called intermittent radials – develops, making a joint like a human elbow. The genetic change includes new muscles and joints that occur in limbs but not in the simple fins.

The discovery of scientists has shown that the fish, thought to have lost the machinery needed to develop body parts, actually has an innate ability to form these structures.

Thumbnail-sized zebrafish have become a mainstay of genetic research. They are easy to keep in large numbers and breed easily, with a single pair producing hundreds of eggs each week. These fish are also soft and easy to handle, and their eggs and embryos are transparent and easy to examine.

The researchers randomly mutated the zebrafish genes and then systematically screened the fish to find those that had undergone interesting shape changes – in this case the bare structures.

With more research, this genetic link between fins and limbs may shed light on how some animals made the transition from sea to land and what genetic mechanics are needed to make this happen.

One question the team hopes to investigate next is whether the new bones change how the zebrafish’s fins function and how the fish move.

“That such complex and coordinated changes may result from the alteration of a single letter of DNA was quite shocking, and it appears that our fish-like ancestors have the raw genetic material and the latent ability to create limbs,” Hawkins said. .