When you look up at the sky, the space around the earth may seem as clear as a song, but there’s a lot going on there that we can not see. In recent years, sin studying radiation through the Earth’s magnetic field has found something peculiar – electrons zipping near the speed of light.

This alone is not the peculiar part; electrons of near light speed, or relativism, are well known in the cosmos, amplified by cosmic particle accelerators. The strange thing was that occasionally extra fast, ultrarelativistic electrons appear – but only during some solar storms, and not others.

A team of scientists led by space physicist Hayley Allison of the GFZ German Center for Earth Sciences in Germany has just figured out why. And it all has to do with invisible, particle-filled radiation belts orbiting the earth.

Only if plasma in a radiation belt is significantly depleted before a solar storm can reach the electrons at the ultra-relative velocity, the researchers found.

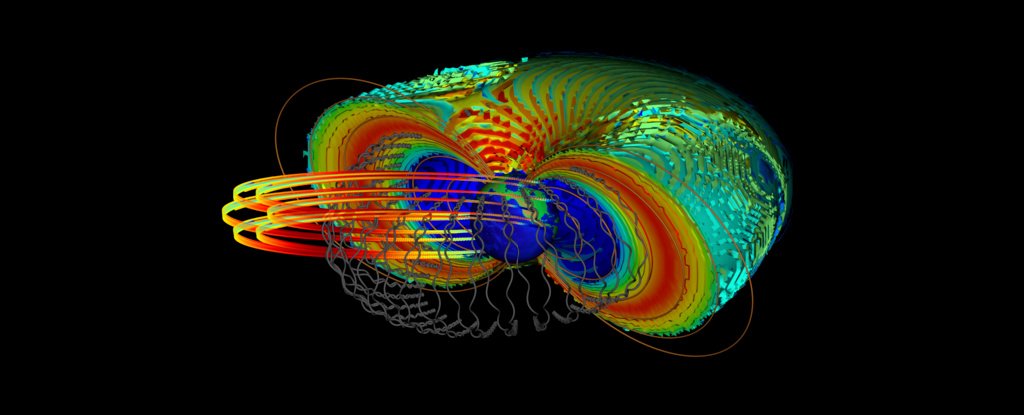

Officially known as Van Allen radiation belts, these belts are located in the pocket of space almost immediately around the earth. The inner belt extends from 640 to 9600 kilometers (400 to 6,000 miles) and the outer belt from about 13,500 to 58,000 kilometers. What these are are areas in which the Earth’s magnetic field captures charged particles from the solar wind.

Here on earth, these regions will not noticeably affect our daily lives (although we would certainly notice if it disappears and the solar wind can free us freely with charged particles), but the area of space immediately around the planet, to a height of about 2000 kilometers, this is where we place most satellites. It is useful to know what kind of space weather can produce ultra-relative electrons.

When accelerated to such high speeds, these electrons become a danger. Because of their high energy, even the best shielding can not withstand them, and their charge when they enter spacecraft can destroy sensitive electronics.

So Allison and her team investigated the analysis of data from the Van Allen probes. Twin spacecraft were launched to study the Van Allen tires in 2012 (before being deactivated in 2019).

During this time, sin recorded several solar storms, intense events in which an eruption of the sun penetrated the earth’s magnetosphere with solar wind and radiation.

They tried to discover why some of these storms led to ultra-relative electrons, and others did not. They especially wanted to investigate the plasma.

It is known that plasma waves – fluctuations in the electric and magnetic fields have an accelerating effect on electrons, which can “surf” through the plasma waves like a wax surfer uses water waves to accelerate.

And it is known that solar storms generate plasma waves around the earth; in fact, the Van Allen probes contributed to the discovery that the so-called “chorus” plasma waves around the earth can accelerate electrons, although the effect alone is considered insufficient to explain the observed ultra-relative electrons. Researchers thought there should be some sort of acceleration process in two steps.

So the team compared plasma observations taken by the Van Allen probe to the solar storms, with and without ultra-relativistic electrons, in an attempt to find out what’s going on.

Plasma density is difficult to measure directly, but the team was able to deduce the density from the fluctuations in the electric and magnetic fields. And the researchers found that the ultra-relativistic electrons both correlate with an extreme depletion of the plasma density and the presence of choral waves.

This is a result that shows that a two-stage acceleration process, as previously thought responsibly, is not necessary for ultra-relativistic electrons.

Although the team focused on the most extreme electron velocities, they also found that when the plasma density was lower, the choral waves accelerated the electron at relative velocities on shorter time scales than when the plasma density was higher.

“This study shows that electrons in the Earth’s radiation belt can be rapidly accelerated locally to ultralelativist energies, if the conditions of the plasma environment – plasma waves and temporarily low plasma density – are right,” said physicist Yuri Shprits of the GFZ German Center for Geosciences explained. and the University of Potsdam in Germany.

“The particles can be considered as surfing on plasma waves. In areas with an extremely low plasma density, they can only extract a lot of energy from plasma waves. Similar mechanisms may be at work in the magnetospheres of the outer planets such as Jupiter or Saturn and in other astrophysical objects. “

The research was published in Scientific progress.