About 100,000 years ago, an extended family of 36 Neanderthal people walking along a beach, with the children jumping and frolicking in the sand, scientists report after analyzing the petrified footprints of beachgoers in what is now southern Spain.

“We have found some areas where different small footprints appear in a chaotic setting,” said Eduardo Mayoral, a paleontologist at the University of Huelva and lead author of the study, which was published online in the journal on March 11. . Scientific reports.

The footprints “may indicate a passageway of very young individuals, as if playing on the shores of the nearby area with stagnant water or wandering around,” Mayoral said in an email to Live Science.

Related: See photos of our closest human ancestor

In June 2020, two biologists discovered the tracks on Matalascañas Beach, in Doñana National Park, after a period of intense storms and high tides.

The biologists first saw petrified animal tracks; some of the footprints were made long ago by large animals, such as deer or wild pigs, Mayoral said.

Only later, after Mayoral’s team analyzed the prints, did anyone realize that some were Neanderthal footprints, he said. “No one at the time acknowledged the existence of the hominid footprints, which were only discovered by my team two months later, when we began to study the entire surface in detail.”

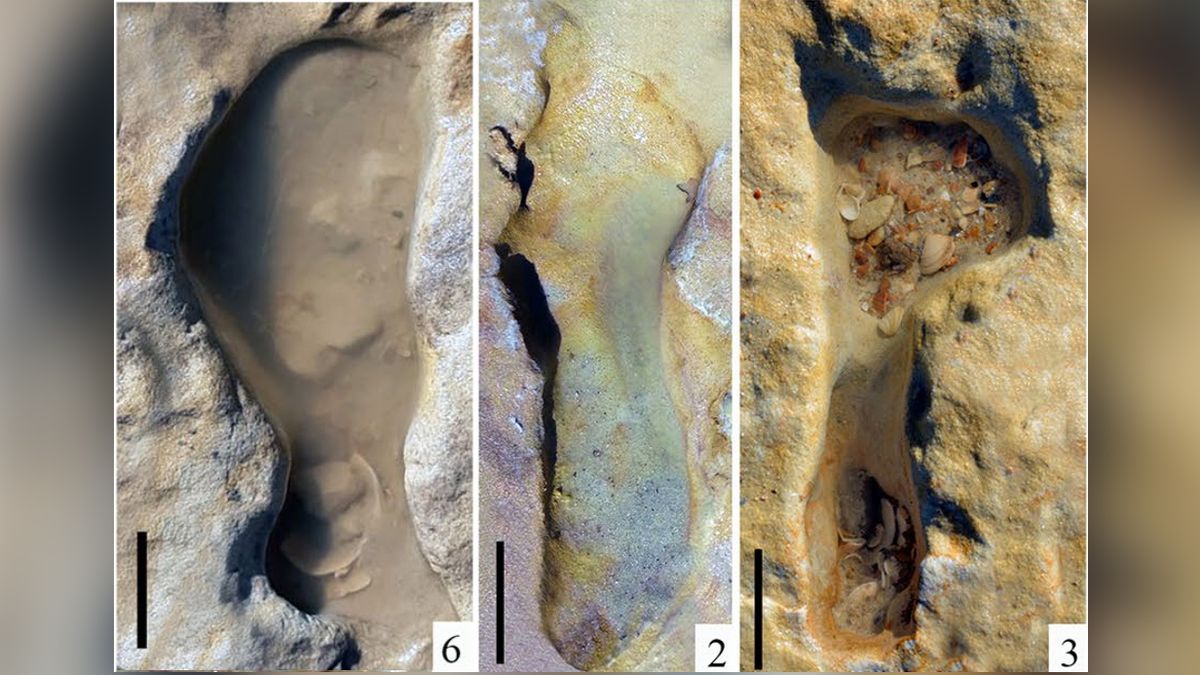

Mayoral and his colleagues identified 87 Neanderthal footprints in the sedimentary rock on the beach of Matalascañas. (The researchers determined that the prints were made by 36 individuals.)

The exposed surface dates from the Upper Pleistocene period, about 106,000 years ago, when ancient stone tools discovered nearby showed that the region was inhabited by Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis). These hunter-gatherers lived between 400,000 and 40,000 years ago in Europe and the Middle East, while early modern humans (Homo sapiens) arrived there about 80,000 years ago. According to the researchers, the tracks may be the oldest Neanderthal footprints ever found in Europe.

At the time the footprints were made, it appears the surface now exposed along the banks of a waterhole was slightly inland from the coast, which at the time was further south than it is today, Mayoral said.

“Probably the water would not have been fresh, but somewhat brackish, as we found evidence of sea salt crystals (halite) on the surface where the footprints were found,” he wrote in the email.

Related: In photos: Neanderthal funerals unveiled

The team expanded the site with an aircraft drone and digitally scanned each of the petrified human footprints in three dimensions.

The size and distribution of the footprints indicate that it was made by a group of 36 individuals who were probably related, including 11 children and 25 adults – five women, 14 men and six individuals of indefinite gender.

“It can be established by correlation with other European sites that there is a direct link between the size of a footprint and the age of the individual who manufactured it,” Mayoral said.

Most adults walking on the beach would have been between 1.3 and 1.5 meters long, but it looks like four prints were made by a person who was 1.8 meters tall. It is higher than the expected height of Neanderthals, so the print was made possible by a shorter individual with a heavy gait, the researchers wrote.

Play in the sand

Of particular interest are the two smallest footprints, about 14 centimeters long, which were presumably made by a child of about 6 years. It is one of several footprints chaotically grouped in some areas, possibly because Neanderthal children played in the sand on the banks of the waterhole, Mayoral said.

Analysis of the tracks shows that most of the footprints are located at the edge of the flooded area, but the individuals who made the prints did not move completely in the water, the researchers wrote.

‘It could involve a hunting strategy to stalk animals in the water [such as] waterfowl and waders or small carnivores, ‘they wrote.

The tracks can also be made by people fishing in the watering hole or looking for shellfish; evidence of similar hunting-and-gathering behavior by Neanderthals has been reported in other ancient sites.

Stone tools attributed to Neanderthals showed up at nearby sites, but in those cases there was no direct evidence – such as Neanderthal bones or teeth – to confirm their presence, Mayoral said.

This made the petrified footprints particularly important, the researchers wrote: “The biological and ethological information of the ancient hominin groups when there are no bone remains is provided by the study of their fossil footprints, which gives us certain ‘frozen’ moments of their exist.”

‘The footprints were an indisputable proof of the existence of these hominids in the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula and specifically in this area of the Andalusian coast,’ Mayoral said.

Originally published on Live Science.