At the end of December, the West African nation of Guinea injected 25 of its senior officials with doses of Russian Sputnik V COVID-19 vaccine. Unshaken by security concerns, national leaders turned to state TV to celebrate.

“We are the guinea pigs,” said one.

Nearly a month later, not a single dose of licensed Western vaccine has been administered on the African continent – even though about 60 million doses have been given worldwide.

This drastic difference is an outcome that public health experts have long feared. It also highlights the enormous challenge facing the global coalition known as COVAX, which seeks to secure vaccine doses for the poorest countries in the world.

“The price of not solving the problem of distributing vaccines internationally will be measured in lives,” said Thomas Bollyky, director of the global health program at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Even before the advent of vaccines, the spread of the coronavirus exposed the benefits that rich countries enjoy in securing critical resources such as hospital ventilators and personal protective equipment for medical workers.

The same dynamic has accumulated in the global race for vaccine doses.

A small group of rich countries – which make up only 16 percent of the world’s population – have confined 60 percent of the global vaccine supply, according to Duke University’s Global Health Institute.

Canada has already ordered enough potential doses to vaccinate its entire population, according to the institute, and the U.S. has enough buying options to vaccinate every American nearly five times.

The accumulation of vaccine doses has left the rest of the world scrambling.

Australia, Canada and Japan are responsible for 1% of coronavirus cases worldwide, Bollyky said, but they have collected more doses than the whole of Latin America and the Caribbean, which have almost 20% of cases. The coronavirus mortality rate in Africa rose to 2.5% this week, officials said, dwarfing the US rate of 1.7%.

“What has happened here is that nations have decided to be more concerned about the reactions of their people at home rather than necessary to bring this pandemic under control,” said Bollyky, author of the book “Plagues and the Paradox of Progress “, said. . ”

This ‘vaccine nationalism’ has serious consequences, according to public health experts such as dr. Larry Brilliant.

Brilliant, a leading epidemiologist who helped eradicate smallpox, said the accumulation of vaccines by rich countries could cause a tragic boomerang effect.

“Being at the forefront of the queue does not help you as much as making sure everyone gets along,” says Brilliant, the founder and CEO of Pandefense Advisory, a group of experts who run the Covid-19 combat pandemic.

“Until everyone in the world is safe, no one is safe,” Brilliant added. “It’s a pandemic. If one country is not vaccinated, this disease will bounce back and forth. And all of us will be constantly besieged by it. ”

COVAX was formed for this very reason.

The initial goal of the coalition, which includes global health groups such as the World Health Organization and more than 190 countries, is to buy 2 billion doses by the end of 2021 to vaccinate 20% of the population in the approximately 100 poorest countries.

“This is the biggest logistical challenge on a scale we have not seen before in global public health,” said Gian Gandhi, UNICEF COVAX Coordinator. This leads to the group’s efforts to buy and deliver vaccines.

The total cost is expected to be up to $ 17 billion, Gandhi said, but the coalition has only $ 2 billion on hand and has not yet received a single dose of coronavirus vaccine, despite the fact that agreements exist for 1.97 million to ensure doses.

However, COVAX made further progress this week.

The coalition on Friday announced the signing of a pre-sale agreement with Pfizer for up to 40 million doses of the vaccine. COVAX also said it would use an option to receive its first 100 million doses of AstraZeneca vaccine.

And earlier this week, newly elected President Joe Biden announced that the US would re-establish ties with the WHO and join the COVAX coalition, in a reversal of the Trump administration’s policy.

But the coalition still needs billions of dollars short of the money it needs to achieve its ambitious goal.

“It does not have the funding and the resources it needs,” Brilliant said.

The COVAX initiative was born in part from a history lesson – an effort by the global community to prevent rich countries from monopolizing vaccines in bilateral transactions, as in 2009 with the swine flu vaccines.

The concept looks like a funding pool, where members pay into a central fund in exchange for enough vaccines to immunize 20 percent of their population.

For rich countries that can afford to negotiate their own stock, it is assurance in the event that a candidate for vaccine they pre-ordered is not approved by regulators. But for the poorest countries in the world, COVAX is a lifeline – the only viable way to receive vaccine doses.

The distribution of COVAX will run out of the largest humanitarian warehouse in the world, a donation from the Danish government to UNICEF. The space spans three soccer fields, higher than a middle building with commodities ranging from syringes to therapeutic food, soccer balls to water drilling rigs.

A box of stock can travel from the center of Copenhagen to anywhere in the world within 72 hours. The vaccines – once secured – will be shipped directly by the manufacturers.

While the world’s affluent countries are accumulating vaccines, COVAX has pleaded for donations of viable doses from affluent countries – the sooner, the better.

“If there are vaccines that are unused and stored for a rainy day, they need to be donated because more can be produced,” said Gandhi, head of market formation and financing for UNICEF suppliers.

Both Canada and the European Union have said they are willing to donate excess vaccines, but nothing has been tied up. According to UNICEF, COVAX has not received any donations.

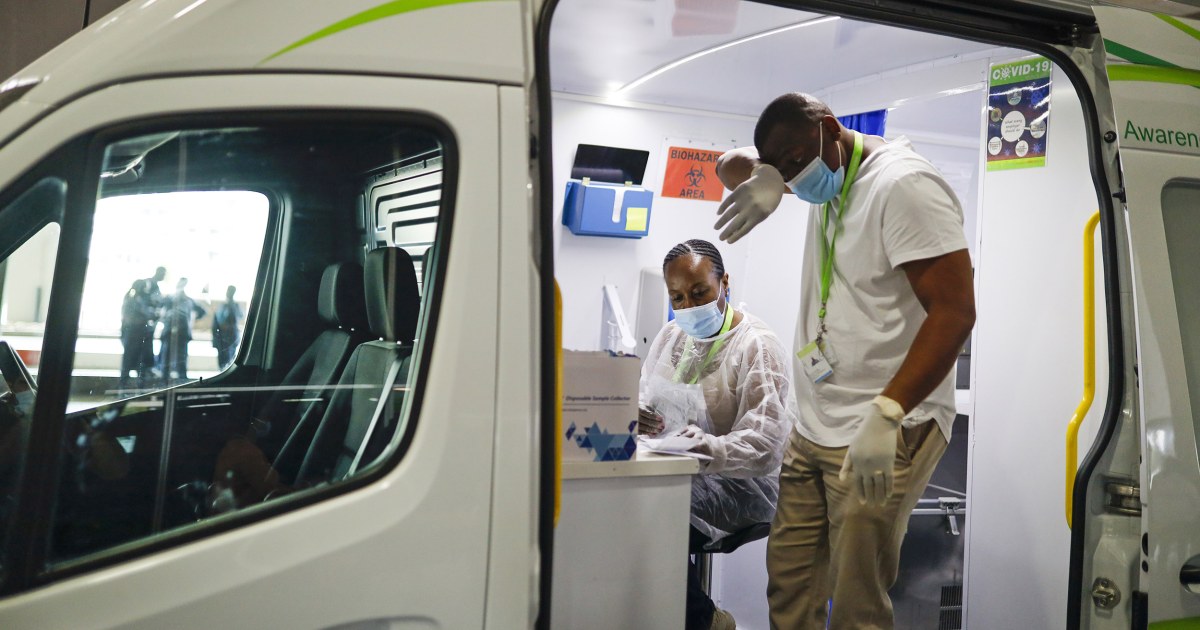

Meanwhile, some countries struggling to access vaccines are doing what Guinea has done, and are turning to less regulated vaccines from China and Russia.

The state-subsidized doses already have consumers in more than a dozen different middle-income countries, including Argentina, Mexico, Turkey, Brazil and Egypt.

“The challenge we have with COVAX is that it is currently a charity,” Bollyky said. “At the end of the day, charity will seem like a second-order cause to many politicians and national leaders.”

“Until we realize that it is in our own interest to make this initiative a success. we are not going to see the kinds of investments and the behavior of national leaders that we need to see to make progress, ”Bollyky added.

One such argument is purely economic. According to RAND, global GDP will drop nearly $ 300 billion each year if only high-income countries can vaccinate, with $ 30 billion in losses specifically for the US. But if high-income countries pay for vaccines, they would get back $ 4.8 dollars for every $ 1 spent, according to the policy firm.

There are also many secondary consequences if developing countries are left unprotected. Failure by COVAX to vaccinate frontline health workers in developing countries could disrupt years of vaccination programs, Gandhi said, which could lead to diseases such as measles and polio that eradicate the world nearby.

But the biggest consequence of an unequal global vaccination is a prolonged pandemic. Failure to vaccinate in Mali or Mozambique could mean a revival of the virus in America, endangering a large number of people who cannot or will not get the vaccine, such as children and immune users.

“No child and no individual is safe,” Gandhi said, “until everyone is safe.”