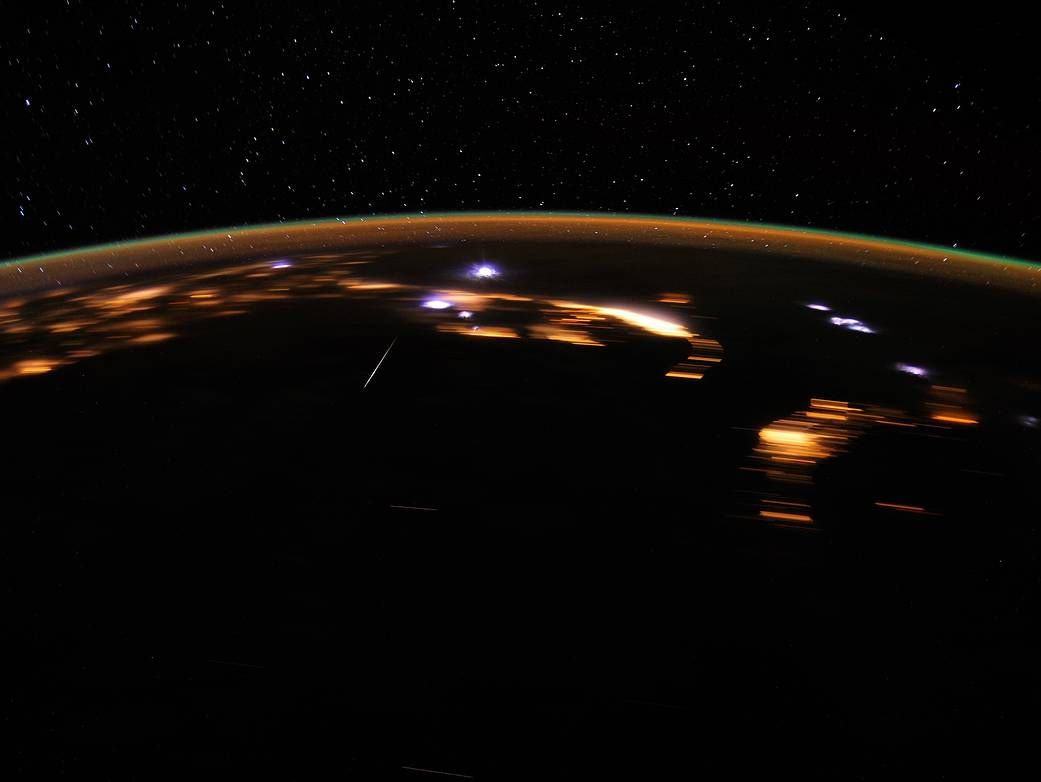

It’s almost time for the Lyrids, the meteor shower that originated in the tail of a comet that surrounds the sun every 415 years.

The comet may be a rare sight, but the earth runs through debris in late April every year. This year, the medium bright meteors that occur when the debris streaks through the atmosphere are visible in the Northern Hemisphere between April 16 and April 30.

Look around at 22:30 local time wherever you can spot a dark sky with little light pollution. The moon will be lush this year during the Lyrids, with a full moon on April 26, meaning that pollution of the moon will be a problem for aerial viewers. The best viewing, according to NASA, will be after the moon sets and before the sun rises. Getting up early can be better than getting up late – on April 20 in New York, for example, the crescent moon will set at 2:48 a.m. and provide a viewing window until sunrise at 6:09 p.m.

The Lyrids are apparently derived from the constellation Lyra, northeast of the bright star Vega. Lyra looks like a skewed square. However, it is not necessary to look straight at Lyra, because through the angle of incidence the meteorite tails will look shorter. To get the best view of long-tailed meteors, lie on your back with your feet to the east and try to get such a wide view of the sky. Give your eyes 20 to 30 minutes to adjust to the darkness to see dimmer meteors.

The Lyrids usually produce 10 to 20 meteors per hour, although they can sometimes erupt with a burst of 100 or so hours. According to NASA, such eruptions were recorded in the United States in 1803 and 1982, in Greece in 1922 and in Japan in 1945.

The Lyrids are fragments from the tail of Comet Thatcher, a comet discovered in 186. Thatcher, however, through the solar system for much longer than that: The first observation of the meteor shower was in China in 687 BC, making the Lyrids one of the oldest meteor showers known.

If you miss the Lyrids, the next chance to see a meteor shower will follow soon. On May 6, the Eta Aquarids will reach a climax. They are best viewed closer to the equator, but offer a view of 10 to 30 shooting stars per hour on the northern latitudes, according to the American Meteorological Society.

Originally published on Live Science.