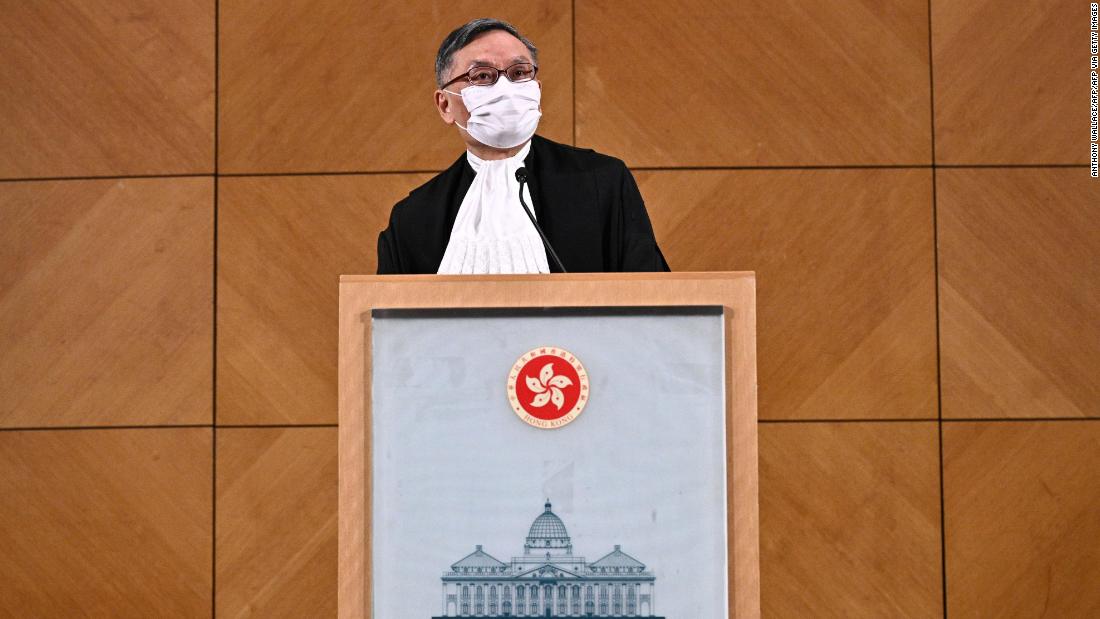

Chief Justice Andrew Cheung wore a black robe, white collar and a white face mask in the city. Chief Justice Andrew Cheung acknowledged the strangeness of the circumstances when he addressed a small audience of judicial officials and others who watched online.

“The Covid-19 pandemic has taken a huge toll everywhere,” Cheung said. “The judiciary and its operations have also been affected, and we must thank our legal staff who have worked so hard in such difficult circumstances to make the courts function.”

That law criminalizes acts of secession, undermining, terrorism, and collusion with foreign powers, and carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment.

Such vague parameters have given authorities the power to tackle opponents against the government as Beijing continues to tighten its control over the alleged semi-autonomous city. Hong Kong officials had earlier promised that the law would come into force and target only a small number of fringe activists. Critics, however, claim that since its inception, the law has been used to forcibly wipe out the city’s previously vibrant pro-democracy movement.

With both the legislature and the administration at the lock of Beijing, the courts are the one branch of government that retains a degree of autonomy – but one that can be tested by the blunt instrument of the security law.

In his speech, and subsequently at a press conference, Cheung avoided discussing the details of the law, arguing that it was inappropriate, as it will be discussed in court soon. But he kept coming back to one important point.

“It is my mission to do my best to uphold the independence and impartiality of the Hong Kong judiciary,” Cheung told reporters. “This is my mission, and I will do my best to fulfill that mission.”

Such independence could be tested a lot in the coming year, and if lost, could cost Hong Kong its legal system and fundamental freedoms. In a speech following Cheung’s, Philip Dykes, head of the city’s bar, remarked that ‘without judicial independence, a pearl of expensive price, we can just as well pack our bags and take them away, because Hong Kong is nothing without not.’

Rule of law

When Hong Kong was handed over to the People’s Republic of China in 1997, the city’s new rulers, eager not to disrupt their economic dynamics, were careful to give the importance of the rule of law and independent judiciary to the persistent Success of Hong Kong. under the principle known as ‘one country, two systems’.

Hong Kong’s legal system has not always had the excellent reputation it currently offers. When the British established their colony on the newly occupied territory in 1842, they thought little about how the new Chinese subjects of the crown would gain access to the law.

“In colonial Hong Kong, racial activity and prejudice contributed to the social injustice inherent in the strong class division in Victorian Britain, and this is reflected in the operation of the courts,” writes Steve Tsang in “A Modern History of Hong Kong: 1841” -1997. “The language of the courts was English, and interpreters were rarely provided – meaning that many Chinese defendants were unaware of what was going on, as they were drawn by an unknown legal system and unsympathetic judges.

Tsang notes, however, that the “rule of law” determined the structure and procedures of the judicial system even in the early years, when there was discrimination, preventing some governors from pursuing certain policies that were detrimental to the local community and helped has wrongly accused the acquittal of many. ‘

After 1997, the rule of law also helped restrict the new rulers of the city. Thanks to its strong protection of speech and assembly, Hong Kong has maintained a lively political and media scene, unlike what has been seen in China, with annual demonstrations – such as the Tiananmen Square massacre on June 4 – marking these freedoms .

But the conflict between the country and the two systems it contains has grown over time and has reached breaking point in recent years.

The prospect of being subject to Chinese justice, through an extradition bill with the mainland, has sparked unrest against the government that upset Hong Kong in 2019. Yet, while the protest actions were successful in defeating the proposed legislation, it also led to the eventual introduction of the National Security Act last year, which led to a number of political crimes and the protection afforded in Basic Law, the de facto constitution of Hong Kong, undermined, while also creating the possibility that accused may in some circumstances be transferred to China for trial.

“We have to defend the city’s rule of law, but we also have to protect the national constitutional order,” Zhang said, adding that many “problems” in the basic legislation that needed to be addressed came to light.

Judicial guard

In his comments this week, Cheung, the new chief justice, apparently addressed these controversies, noting that in some cases judges were “scrutinized” and subject to “biased criticism.”

“While the freedom of speech of all in society must be fully respected, no attempt should be made to exert undue pressure on judges in the performance of their judicial functions,” Cheung said. “Judges must be fearless and willing to make decisions in accordance with the law, regardless of whether the outcomes are popular or unpopular, and whether the outcomes will make themselves popular or unpopular.”

But what exactly the law means could be a gripping target, as Beijing takes a more practical approach to Hong Kong’s legal system.

Under the Basic Law, while Hong Kong has a “court of final appeal”, the true arbiter of the city’s constitution is China’s National People’s Congress, the country’s rubber stamp parliament, which “interprets” various articles of the Basic Law can reach out. – to essentially rewrite it.

In the past, this power was rarely used, but in recent years it has been increasingly exercised. Observers have expressed concern that if the courts in Hong Kong applied the national security law more leniently than Beijing would have wanted, the national government might act to force them to do otherwise.

And when asked about such interventions by the central government, Cheung acknowledged that few judges in Hong Kong could do so. “If there is an interpretation, the court must follow it,” he said.

In an interview this week, Young noted that “central and local governments have full confidence in the new chief justice”, which could prevent an avalanche of interventions in the near future.

“The first group of (security law) cases brought by the courts will be considered by all to be test cases to see the true breadth and limits of the law,” he said. “My prediction is that there will be no direct interference from (Beijing) to influence or change the outcome of these cases.”

Tsang, the Hong Kong historian and director of the SOAS China Institute in London, disagreed and predicted that the chief justice would ‘come under enormous pressure’ in the coming years.

“(It) will be extremely difficult for the chief justice to resist in the long run, which means that the erosion of judicial independence is unfolding, and unless there is a change of government in Beijing that is unlikely to take part,” he said.

But Tsang said Cheung may have put himself in an impossible position when he accepted the role.

“Efforts to protect Hong Kong’s judicial independence are now a backdoor operation, and the Chief Justice’s determination to stand fast or not will only determine the pace of this process,” Tsang said. “It is unlikely that he will be able to keep the line out in the short term, even if he is determined.”

CNN’s Eric Cheung reported.