The idea of a warp that takes us faster than the speed of light across large spaces has long fascinated scientists and scientific fans. Although we are still a long way from any universal speed limit, this does not mean that we will never ride on the waves of the warped space-time.

Now a group of physicists has drawn up the first proposal for a physical warp, based on a concept devised in the 90s. And they say it should not violate any legislation of physics.

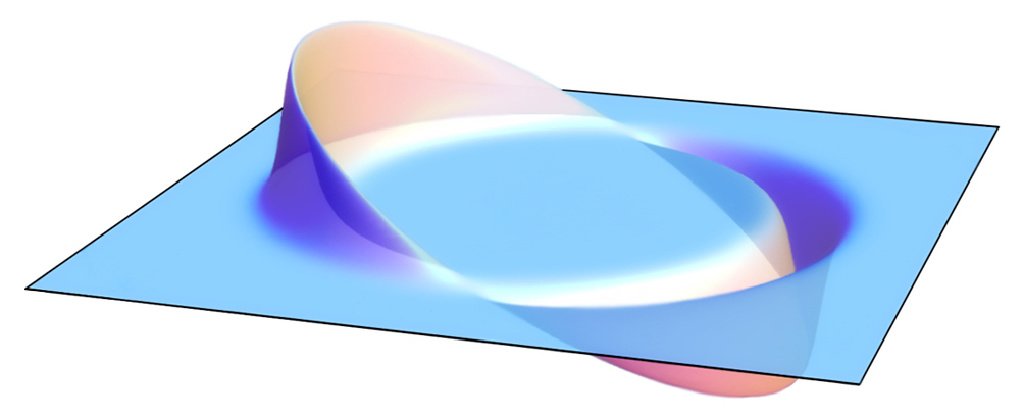

Theoretically, curved drives bend and change the shape of space-time to exaggerate differences in time and distance, which can cause travelers to move faster over distances than the speed of light.

One of these circumstances was explained more than a quarter of a century ago by the Mexican theoretical physicist Miguel Alcubierre. His idea, proposed in 1994, was that a spaCecraft powered by something called ‘Alcubierre propulsion’ can achieve this faster journey than light. The problem is that it requires a lot of negative energy in one place, something that according to existing physics is simply not possible.

But the new study has a solution. According to researchers from the independent research group Applied Physics, based in New York, it is possible to drop the fiction of negative energy and still make a warp, even if it may be a little slower than we would like.

“We have gone in a different direction than NASA and others, and our research has shown that there are actually several other classes of chain drives in general relativity,” says astrophysicist Alexey Bobrick of Lund University in Sweden.

“In particular, we have formulated new classes of formulation solutions that do not require negative energy and therefore become physical.”

Why is negative energy such a big deal? The need for negative energy circumvents some of the common relativity problems of traveling faster than light, in that space can expand and contract faster than light, while everything within the curve remains within the universal speed limits.

Unfortunately, it presents more problems of its own – mainly that the negative energy we need exists only in quantum fluctuations. Until we can find a way to create a mass of the good on the sun, this kind of ride is just not possible.

The new research works around this – according to the article, negative energy is not necessary, but an extremely powerful gravitational field is. The gravity will do the heavy lifting of the bending of space-time, so that the time course inside and outside the chain drive machine would differ significantly.

However, you will not be able to book tickets yet – the amount of mass needed to achieve a noticeable gravitational effect on space-time will be at least planet size, and there are still many questions to be answered.

“If we take the mass of the entire planet Earth and compress it into a shell 10 meters in size, then the correction of the duration within it is still very small, about an extra hour per year,” Bobrick tell New scientist.

Another interesting finding from the research relates to the shape of the warp: a wider, longer vessel requires less energy than a long and thin one. Think of a plate that is thrown upright first, and then you have an idea of the optimal shape of the chain drive.

Although the reality of traveling to distant stars and planets is still far away, the new study is the latest addition to a growing body of research suggesting that the principles of warp propulsion are sound in scientific terms.

The researchers admit that they are not yet sure how to put together the technology they described in their article, but at least there are more of the numbers now. They are confident that the warp drive will become a reality well into the future.

“Although we still cannot break the speed of light, we do not have to become an interstellar species,” says Gianni Martire, one of the scientists at the Applied Physics group behind the new study. “Our research on warp fabrics has the potential to unite us all.”

The research was published in Classical and quantum gravity.