Two clinical trials suggest that specific antibody treatments may prevent deaths and hospitalizations among people with mild or moderate COVID-19 – especially those at high risk of developing serious diseases.

One study found that a coronavirus antibody developed by Vir Biotechnology in San Francisco, California and GSK, headquartered in London, reduced the chance of hospitalization or death among participants by 85%. In another experiment, a cocktail of two antibodies – bamlanivimab and etesevimab, both made by Eli Lilly of Indianapolis, Indiana – reduced the risk of hospitalization and death by 87%.

The study results, both announced on March 10, come from randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trials, but have not yet been published. This adds an increasing amount of evidence that the treatments can help ward off serious illnesses if administered early, says Derek Angus, an intensive care physician at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania.

The antibodies “appear to be incredibly effective,” he says. “I am very excited about the results of these trials.”

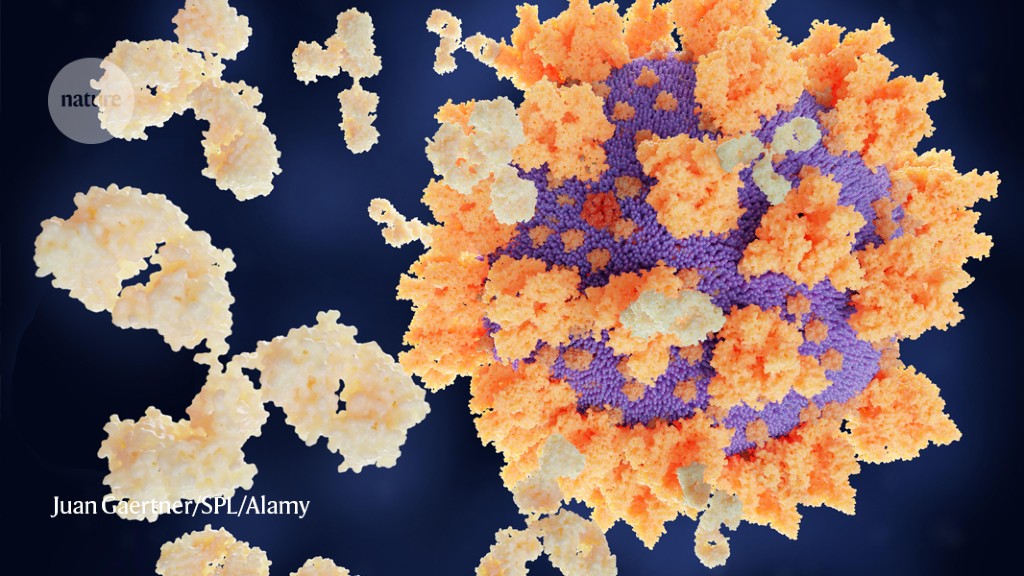

The body’s natural response to viral infection is to generate a variety of antibodies, some of which can directly interfere with the virus’ ability to replicate. In the early days of the pandemic, researchers rushed to identify and produce in large quantities the antibodies that are most effective against the coronavirus. The resulting ‘monoclonal antibodies’ have since been tested in different environments as treatment for COVID-19.

For and GSK’s antibody, called VIR-7831, was first isolated in 2003 from someone recovering from severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), caused by a similar coronavirus. It was later found that the antibody also binds to the SARS-CoV-2 ‘spike’ protein.

The companies also announced that in laboratory studies1, VIR-7831 bound to SARS-CoV-2 variants – including the rapidly spreading 501Y.V2 variant (also called B.1.351) first identified in South Africa. They attribute the resilience of the antibody to the target: a specific region of the protein that is not prone to mutations.

Low recording

VIR-7831 joins a list of monoclonal antibodies tested against COVID-19, some of which – including the Lilly combination – have already been authorized in the United States and elsewhere. But there is relatively little admission by U.S. doctors and their patients, Angus says.

One problem, he says, is that although results have been published and submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, companies do not yet have to publish data from key clinical trials in peer-reviewed journals. The medicine is also expensive and must be administered by infusion into a specialized facility, such as a hospital or outpatient treatment center. This is a difficult task if medical resources have already been expanded through a boom in the cases.

Another challenge is mixed messaging. Earlier in the pandemic, some important clinical trials with people admitted to hospital with COVID-19 found no benefit from monoclonal antibodies. Many researchers expected the result: monoclonal antibody therapy is expected to work best early in the disease, and the late stages of symptoms of severe COVID-19 are sometimes more driven by the immune system than by the virus.

Nevertheless, the clinical trials created a story that competed with positive results in studies of milder infections, says Angus, which sparked skepticism. “People would say, ‘But I thought it was not working,'” he says. “It’s getting in the way completely.”

And while studies on mild infections show promise, they are too small to draw definitive conclusions for researchers, says Saye Khoo, a pharmacologist at the University of Liverpool, who leads the UK AGILE Coronavirus Drug Testing Initiative. Only a small fraction of people with a mild COVID-19 will lead to serious illness, which means that although the trials enrolled hundreds of participants, the number of people admitted to hospital or dying was low.

But it will take a long time until everyone is vaccinated, and monoclonal antibodies can provide an important bridge between vaccines and the treatments found for people admitted to hospital, says Jens Lundgren, a doctor at the University of Infectious Diseases. of Copenhagen and Rigshospitalet. “It’s not a substitute for vaccines, but it’s a plan B,” he says, adding that the drugs may be especially important for those who may not have an immune response to vaccination.

The speed with which these monoclonal antibodies were developed holds a lesson for future pandemics, Khoo says. “These connections are undoubtedly exciting,” he says. “We must not forget this, because other pandemics will come to us. It was a real lesson in how to be prepared. ”