The poster was not the funniest marketing campaign, but it made its point: “Come get your eggs !!!”

Every person over the age of 60 who received a COVID-19 vaccine at this Beijing community center would be entitled to two boxes of free eggs. The agreement was part of a nationwide effort to increase vaccination rates in a country where the successful suppression of the pandemic has sparked discontent, despite adequate vaccine supplies.

Chinese authorities have set a target to vaccinate 40% of the 1.4 billion population by June. According to health authorities, nearly 180 million doses were administered on April 14, although the number of fully vaccinated people is unknown.

To achieve their goal, authorities have sent community-level workers across the country to knock on the door, broadcast calls on the town’s speakers and offer vaccination benefits.

Free eggs and parking tickets were a common offer in Beijing. In one district of Shenzhen, companies donated 2,500 coupons for fried pigeon and free soy milk to entice people to roll up their sleeves. In another film, patriotic films were shown that ‘warm the hearts’ of those who have been vaccinated.

One reason for the initially slower vaccination of China is its success in stopping the spread of the virus. China has had only a handful of small outbreaks this year, which were quickly prevented by severe blockades and quarantines. Most of the country has been living normally for months, with group meetings, open schools and workplaces and little sense of urgency around vaccination.

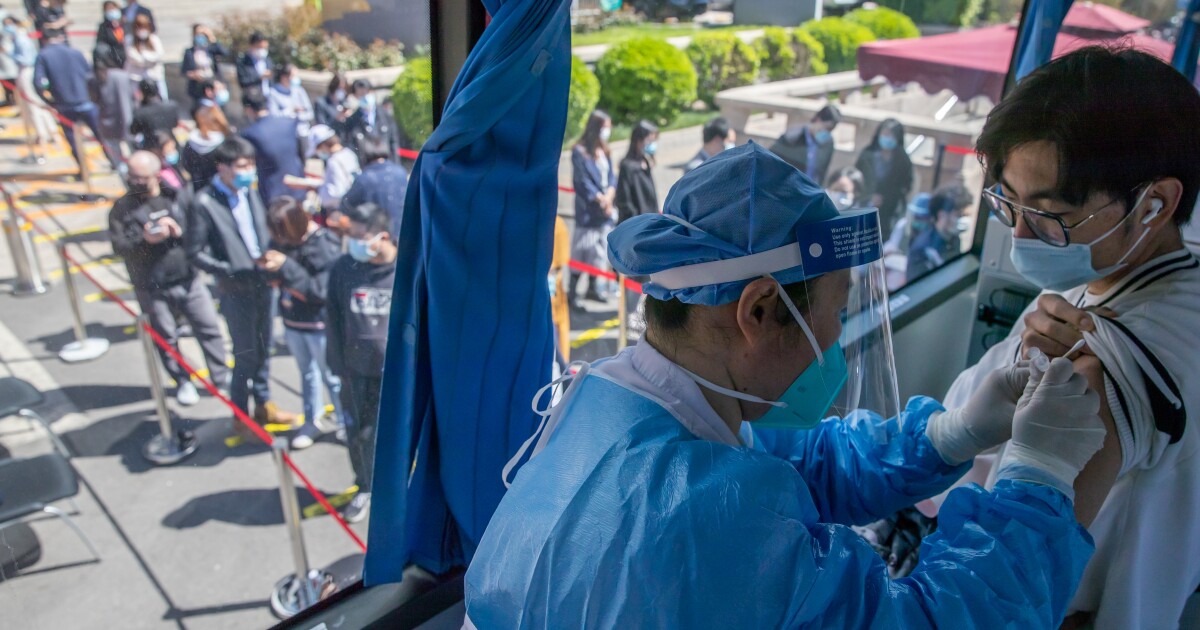

Residents stand in for a vaccination at a shopping area in Beijing. China is accelerating its vaccination campaign by offering incentives – free eggs, shopping vouchers and more – to those who get a chance.

(Ng Han Guan / Associated Press)

At the same time, there was some skepticism about the effectiveness of China’s vaccines, which were sent to dozens of countries as part of Beijing’s vaccine diplomacy, although the manufacturers did not release any public data on their final trials.

Experts from an advisory panel of the World Health Organization recently said that they saw data from Chinese companies Sinopharm and Sinovac that their vaccines meet the WHO requirements of 50% efficacy and full safety. The data were not made public, but Sinopharm claimed its vaccination was 79%, while Brazil, Turkey and Indonesia said Sinovac trials in their countries showed 50% to 83% effectiveness.

On April 10, Gao Fu, head of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, shocked some in the government when he told a news conference that the effectiveness of China’s vaccines was “not high” and that it could improve is changed by adjusting the number of doses, the amount of time between doses or mixing different types of vaccines.

He also stated that mRNA vaccines – the kind produced in the US by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna – have reached remarkable levels of immunity and that China should not overlook such technologies. It was a scientific observation that immediately became political. Gao was factually correct: China’s vaccines have lower efficiencies than those manufactured by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna.

But to say so in China’s hyper-nationalist environment, where vaccines have become a symbol of the country’s scientific prowess and global influence, has been controversial. Chinese officials and state media have in recent months questioned the safety of foreign vaccines while promoting China’s supply, despite the lack of transparency surrounding their trial data.

Gao will soon be quoted again in the media with the state, saying foreign coverage of his recognition that Chinese vaccines offer less protection is a ‘complete misunderstanding’.

At the community vaccine in Beixinqiao, a district in central Beijing, no one seemed to have heard of Gao’s statements or was discouraged from being vaccinated.

“I believe our country will ensure the safety of its people,” said Cui, 28, a woman who just got her second shot and did not give her full name.

A work uniform stands outside a vaccination yard in Beijing COVID-19 with a sign displaying the slogan ‘Timely vaccination to build the Great Wall of Immunity’.

(Ng Han Guan / Associated Press)

A volunteer named Qi Chao (40) stood in the stairwell of the building and held up QR codes to scan and register visitors. They came in a steady stream: a young woman helping her brilliant father report on his cell phone, a street sweeper still in her uniform, a woman with a plastic bag of vegetables standing outside and shouting questions at her friend had before she entered.

Some visitors had questions about their eligibility – a breastfeeding mother, an elderly woman with an arm injury, a man with high blood pressure – but they were few. Qi, the volunteer, said almost no one asked what vaccine they were getting, or inquired about its effectiveness.

“In any case, there is no difference between the vaccines,” Qi said. “I do not know how long it takes, how well it works, but it is of course useful to get it and better to have it than not.”

Scientists agree.

“Protection is much better than having no protection,” said Keiji Fukuda, director of the University of Hong Kong’s School of Public Health. As COVID-19 continues to spread and mutate, it is likely that individuals will need additional shots no matter what vaccine they receive now, he said: “It is better to be vaccinated early with the approved vaccine available.”

Gao’s proposal to mix mixtures – to use different types that stimulate immune responses in different ways – is being seriously considered in several countries. Researchers at Oxford University are testing whether combinations of the Pfizer and AstraZeneca vaccines provide better immunity than any of the vaccines alone. Trials of an AstraZeneca combination with the Russian Sputnik V vaccine are also underway.

Scientists from China’s National Institutes of Food and Drug Control have experimented with combinations of vaccines on mice and found that some produce a stronger immune response.

Gao, the CDC chief, and researchers from the National Institutes for Food and Drug Control did not respond to requests for further comment from The Times. Official guidelines in China recommend that the same vaccine product be used for both shots. But there is a possibility that ‘mixing vaccines’ could pave the way for the use of foreign vaccines in China.

Chinese firm Fosun Pharma has had an agreement with BioNTech since December last year to distribute 100 million doses of the mRNA vaccine it developed with Pfizer. But the continental government has not approved the vaccine, despite WHO approval and separate regulators from Hong Kong and Macao.

Clinical trials with the vaccine are ongoing, but it is unclear whether China will approve it first or prioritize a fully Chinese-made mRNA vaccine.

The Wall Street Journal Friday reported that Chinese officials plan to approve the BioNTech vaccine within the next ten weeks, citing unnamed sources. But that depends in part on the approval of the Chinese vaccine abroad, the Journal reports.

The choice of vaccines is more complicated than the simple comparison of efficacy numbers, said Sheng Ding, director of the Global Health Drug Discovery Institute, a joint venture between Tsinghua University and the Gates Foundation.

Even China’s vaccine with lower efficacy is valuable in preventing serious diseases in those infected, he said. This is more important for individual protection, while higher-efficiency mRNA vaccines may work better to increase herd immunity. The cost of producing, transporting and storing different types of vaccines also influences policymakers’ decisions to use.

Political considerations about saving face should not come into play in a medical context, Ding said. Foreign drugs are widely used in China without politically sensitive implications, he pointed out. Why should vaccines be different?

“At the end of the day, it’s about meeting the needs of the people,” Ding said. After all, it is also a political consideration.

Special Correspondent Ziyu Yang of the Times Office in Beijing contributed to this report.