Early studies have shown that the coronavirus variant that is widespread in California is somewhat resistant to antibodies that fight infection, but the vaccines should still offer a lot of protection, according to experts in infectious diseases.

Antibodies generated by the vaccines, or by previous coronavirus infection, were two to four times stronger compared to earlier versions of the virus compared to the new variant, scientists at UCSF found in laboratory studies. They announced preliminary results this week.

The finding is disappointing, but not worrying, say scientists involved in the study, as well as outside observers. The vaccines are extremely potent, and even with a decrease in antibody strength, they are probably just as effective against the variant as against the original version of the virus with which they were designed.

If there is a reduction in efficacy, the vaccines should prevent almost all cases of serious diseases and deaths, even of the new variant.

“In my opinion, it will make no difference in terms of vaccine efficacy,” said Raul Andino, a UCSF virologist who led the various antibody research. “I would say there is nothing to be afraid of right now.”

The California variant is now predominant in much of the state; there are technically two variants, known as B.1.429 and B.1.427, but they are almost identical and have the same key mutations. Scientists usually study it as a single variant.

Two teams of UCSF scientists this week released study results showing for the first time that the variant looks more contagious than earlier versions of the coronavirus, and that it can also cause serious diseases and resist antibodies.

All the results indicate that this variant is of concern and that it should be closely monitored. The fact that it is so widespread should remind people to be vigilant about wearing masks and to keep social distance, even if the winter thrust fades and the state reopens, experts warn.

But especially the antibody research is important to put in context, scientists say. The investigation itself is critical: if it looks like variant vaccinations could be avoided, public health officials want to know immediately. The vaccine manufacturers also need to know if they need to update their formulas to better suit new variants.

The California variant – together with one from South Africa – can make the vaccines marginally less effective in subtle but important ways. As with so many aspects of this pandemic, scientists will not have all the answers until they do more research.

Studies in South Africa have shown that vaccines work somewhat less well against another variant there. The Johnson & Johnson vaccine, for example – which the Food and Drug Administration is considering for emergency clearance – is approximately 64% effective in South Africa and 72% effective in the United States. Moderna has updated its vaccine to better suit the South African variant after studies found it to be less effective; the new version is still being revised.

Similar studies have not yet been done for the California variant. The presence of antibodies in the laboratory is currently the only sign that there may be problems, but that does not mean that the vaccines will work in real life.

Antibodies are the immune system’s most powerful response to disease – causing pathogens. These are specialized proteins that are released by the immune system to target and kill invaders.

If someone is infected with a virus or other pathogen, the immune system learns from the experience and if it encounters the same virus again, it will quickly accumulate an army of antibodies. Vaccines also replenish the immune system to release antibodies. The vaccines used in the United States cause major antibody responses that are approximately 95% effective in killing the coronavirus.

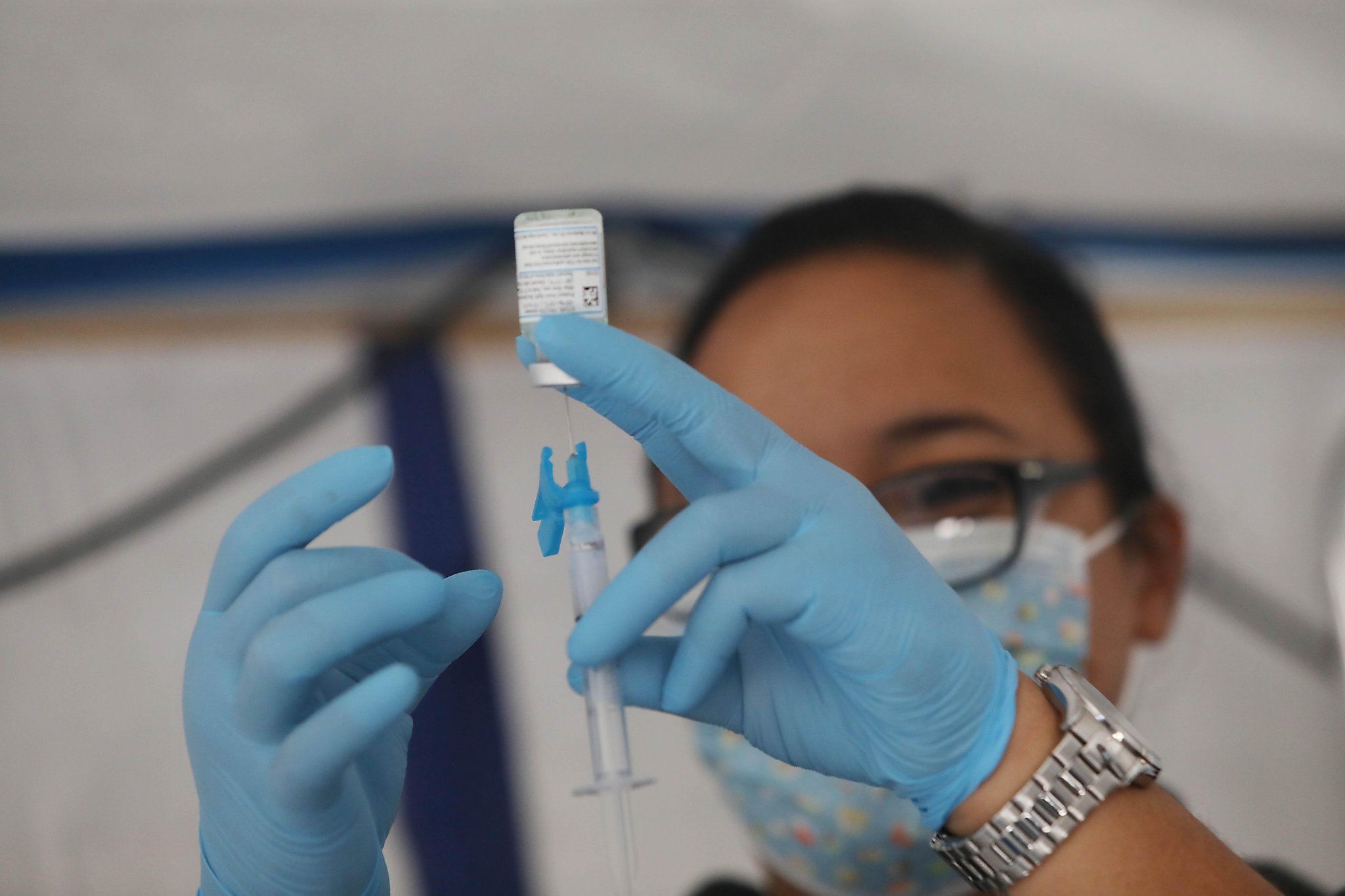

To understand the effectiveness of the antibody against the new variant, UCSF scientists conducted a general experiment called a neutralization assay. They collected antibodies from infected people and others who were vaccinated, and diluted the antibodies to varying degrees.

They soak samples of the California variant and a non-variant virus for half an hour in the different antibody dilutions. Then the antibody-soaked viruses were mixed with cells in petri dishes to test if the viruses were still alive and contagious. Scientists have focused on how much the antibodies can be diluted and still succeed in killing or neutralizing the virus.

The UCSF team found that antibodies generated by the vaccines could be diluted twice as much against the original virus as against the California variant. Antibodies from previously infected people could be diluted four times as much.

In other words, the antibodies were stronger compared to earlier versions of the virus compared to the new variant. Similar studies from South Africa have found that antibodies are six to ten times stronger than the original form of the virus compared to the variant there.

The California variant should be a cause for concern, “but certainly not like South Africa,” says Dr. Jay Levy, an expert in infectious diseases at UCSF, who says he finds the results released this week reassuring. ‘The vaccinations will work unless it changes to get worse. You are still neutralizing the virus. ”

There are several caveats to these early results, the most important of which are laboratory experiments that analyze interactions between the virus and antibodies in a very controlled environment. In real life, the body confirms a complex immune response to the virus. It can be further helped or prevented by environmental factors that cannot be repeated in a laboratory.

The effectiveness of vaccines has also been nuanced. The vaccines used in the United States are almost 100% effective in preventing hospitalization and death of COVID-19, but it is unclear how well it is protected against asymptomatic diseases. Vaccines may still be carriers of the virus. It is also not yet known how long the protection of the vaccine will last.

The key takeaway remains: Everyone should be vaccinated when it’s their turn, said Bali Pulendran, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford.

“If you were to ask me, would you take the vaccine in the hope that it would provide some protection against variants?”, He said. “My answer would be a resounding yes.”

Erin Allday is a staff writer for the San Francisco Chronicle. Email: [email protected] Twitter: @erinallday