WASHINGTON – How low can U.S. emissions be? Under President Joe Biden, the number to look at could be 50 percent.

As he prepares for a global climate summit next month, a powerful campaign of influence is underway over the president’s forthcoming commitment to the Paris Agreement, with all eyes on whether he will promise to emit greenhouse gases by the end of the month. decade by more than less than 50 percent. .

To keep global temperatures in check, the United Nations says the world should almost halve its emissions by 2030 compared to a decade ago. This year, as Biden returns the US to the Paris Agreement, a variety of environmental groups, elected officials and scientists support an American target of no less than 50 percent, a goal the country is nowhere near achieving .

Behind the scenes, some Democrats and European officials are campaigning for an increasingly aggressive promise. However, the administration is getting a setback on the other side of business groups who say 50 percent are unrealistic, especially before Biden can even explain how he will get there, according to interviews with nearly a dozen industry officials, lobbyists and congressional assistants.

And many Republican lawmakers want him to skip the promise altogether, arguing that he will give Beijing a huge economic advantage by painfully curtailing it, while China will increase its emissions.

Senator John Barrasso, R-Wyo., The top Republican on the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, warned that Biden would “set punitive targets for the United States while our opponents retain the status quo.”

This reasoning is completely rejected by scientists and climate activists.

“This is not a moment to hide behind the vanity of other countries,” said Rachel Cleetus of the Union of Concerned Scientists, one of many groups calling for a cut of at least 50 percent.

In his first days in office, Biden committed the United States to neutralizing emissions of heat-trapping gases by 2050. But this is a distant goal that the US will achieve or miss long after he leaves office. The more pressing question is how drastically the US will reduce emissions in the short term.

Under the Paris Agreement, all countries were required to declare updated pledges, known as a ‘nationally determined contribution’, for 2030. As of February, 75 parties to the agreement have done so.

The White House declined to comment on Biden’s decision. However, administration officials said an announcement was expected before or at the World Summit of Presidents and Prime Ministers to tackle climate change, which Biden announced just after taking office and which will be presented on April 22, coinciding with the Earth Day.

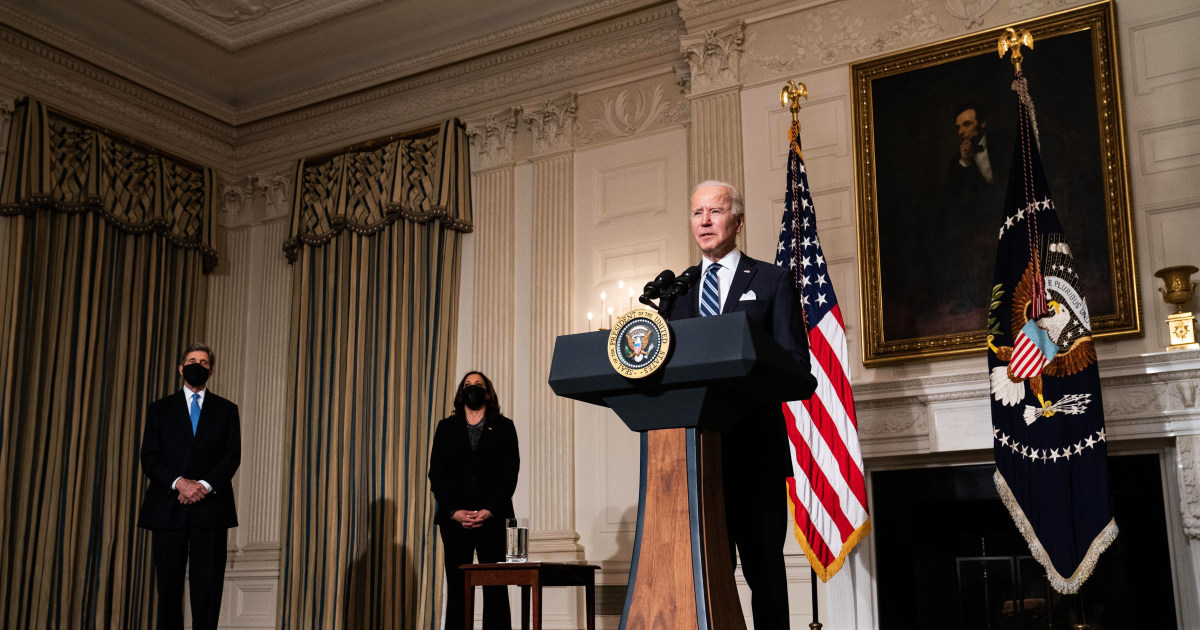

Biden and his special envoy for climate change, John Kerry, hope to use the virtual summit to increase pressure on other polluters to announce their own ambitious promises. Not everyone is invited. Kerry said the 17 countries that will have the largest emissions, along with vulnerable countries that have dramatic impacts on climate change such as Bangladesh and Palau.

Biden’s decision comes as new data shows that the promises so far are “nowhere near the level of ambition” to achieve global targets to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, according to UN Secretary-General António Guterres. The joint pledges would deliver less than 1 percent by 2030, the UN said. Other recent data show that emissions are rising again after a temporary pandemic.

Even with 50 percent, the US would far from set the pace. The European Union has declined at least 55 percent compared to 1990 levels, while the United Kingdom has promised 68 percent.

Climate Action Tracker, an independent scientific group, said this month that by 2030 the US should cut by 57 percent to 63 percent to reach Biden’s goal of zero net emissions by the middle of the century.

In the US, a pledge of 50 percent or more has been accepted by the Environmental Defense Fund, the National Resources Defense Council and the World Resources Institute, along with the “America Is All In” coalition led by UN Special Envoy Mike Bloomberg and Washington Gov. Jay Inslee.

Another looming question: whether Biden can back up his number with details on how he will force the necessary cuts to the biggest emissions sector: transport, electricity and heavy industry.

White House climate tsar Gina McCarthy has drawn up plans, but what is feasible depends heavily on what Biden can get through Congress, perhaps through infrastructure legislation, a question that is unlikely to be resolved before the summit.

“There are so many things that need to be put in place from technology to policy to market mechanisms,” said Marty Durbin, senior vice president of policy of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. “To have a lasting existence, we will need legislation passed by Congress.”

The American Petroleum Institute, the powerful association for oil and gas trade that has so far tried to brand the industry as a positive role in climate change, endorsed ‘the ambitions of the Paris Agreement’, but declined to say how many US should not cut back by 2030.

“The track should be one that balances energy security and environmental goals in terms of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, promoting economic growth and maintaining the competitiveness of the United States,” said Aaron Padilla, who manages API’s climate policy, in an interview. . . “It’s a very delicate balance.”