Gravity wave astronomy is still in its infancy. LIGO and other observatories have opened a new window on the universe, but their gravitational view of the cosmos is limited. To increase our view, we have the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravity Waves (NANOGrav).

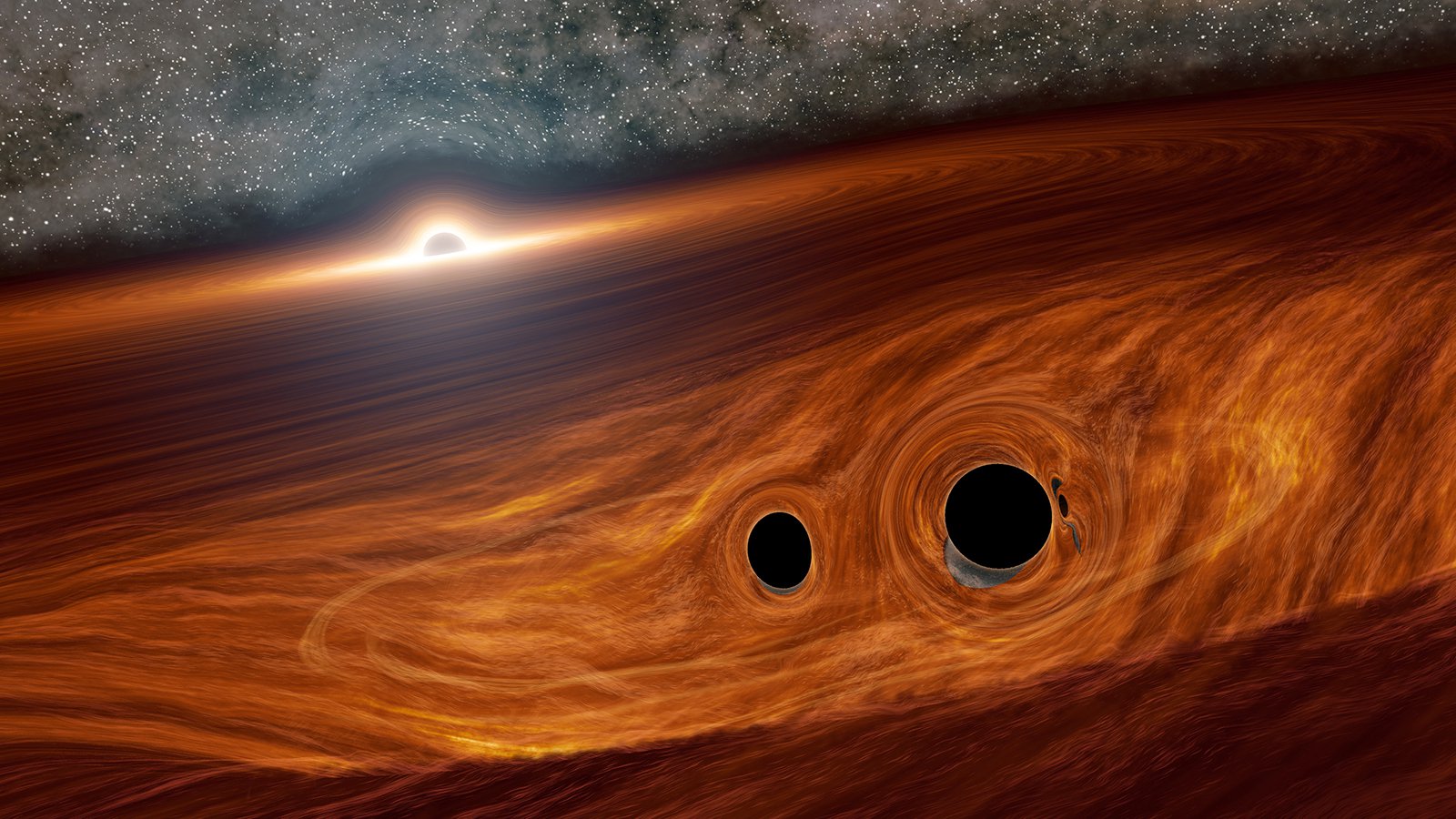

Gravity waves are created by the movement of massive objects. Most of the gravitational waves we have noticed come from the fusion of black holes. In their last moments, binary black holes orbit each other very fast, delivering fast and strong gravitational waves. But most gravitational waves rippling through the universe are not fast or strong. It is the faint echo of black holes that is not about to merge. Their slow orbits create a backdrop of gravitational waves. It can take years before a single wave from one of these sources is a complete cycle.

To detect these gravitational waves, NANOGrav observes radio pulses from fast-rotating neutron stars known as millisecond pulses. Most of these pulses are very frequent, and a change in their pulse rate is caused by a change in their motion relative to the earth. In essence, NANOGrav is like LIGO, but on the scale of our galaxy. But because this background oscillates gravitational waves so slowly, it takes years to observe a shift of the pulses, to observe.

NANOGrav has been looking at pulses for over a dozen years and they have just published some initial results. In the study, the team looked at 45 millisecond pulses that they know are very stable. Some of them have been observed for 12.5 years, but all have been observed for at least three years. When they filtered out false noise effects, they found that it was a background signal of gravitational waves with an oscillation period of about a year. They can not prove that gravitational waves are the origin of this signal, but they have ruled out other possibilities, including any bias in their data.

While a decade of observations seems like a long time, it’s just a moment in time for many of these gravitational waves. To better understand them, we will have to keep looking much longer.

Reference: Arzoumanian, Zaven, et al. “The NANOGrav 12.5-year-old dataset: looking for an isotropic stochastic background with gravitational wave.” The astrophysical journal letters 905.2 (2020): L34.