On December 31, 2020, the law became One Small Step to Protect Human Heritage in Space Law. As for laws, it’s pretty benign. This requires companies that work with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration on lunar transmissions to agree to be bound by otherwise unenforceable guidelines intended to protect US landing sites on the moon. It’s a fairly small pool of affected entities. However, it is also the first law enacted by any nation that recognizes the existence of human heritage in outer space. This is important because it reaffirms our human commitment to protecting our history – as we do on earth with sites such as the Historic Sanctuary or Machu Picchu, which are protected by instruments such as the World Heritage Convention – while also acknowledging that the human species is expanding. into space.

I am a lawyer who focuses on space issues who want to ensure the peaceful and sustainable exploration and use of space. I believe that people through space can achieve world peace. In order to do so, we must recognize landing sites on the moon and other celestial bodies as the universal human achievements that they are, based on the research and dreams of scientists and engineers who have stretched across this globe over the centuries. I believe that the One Small Step Act, enacted in a divisive political environment, shows that space and preservation are truly non-partisan, and even unifying principles.

It’s just a matter of decades, maybe just years, before we see a continuous human presence on the moon.

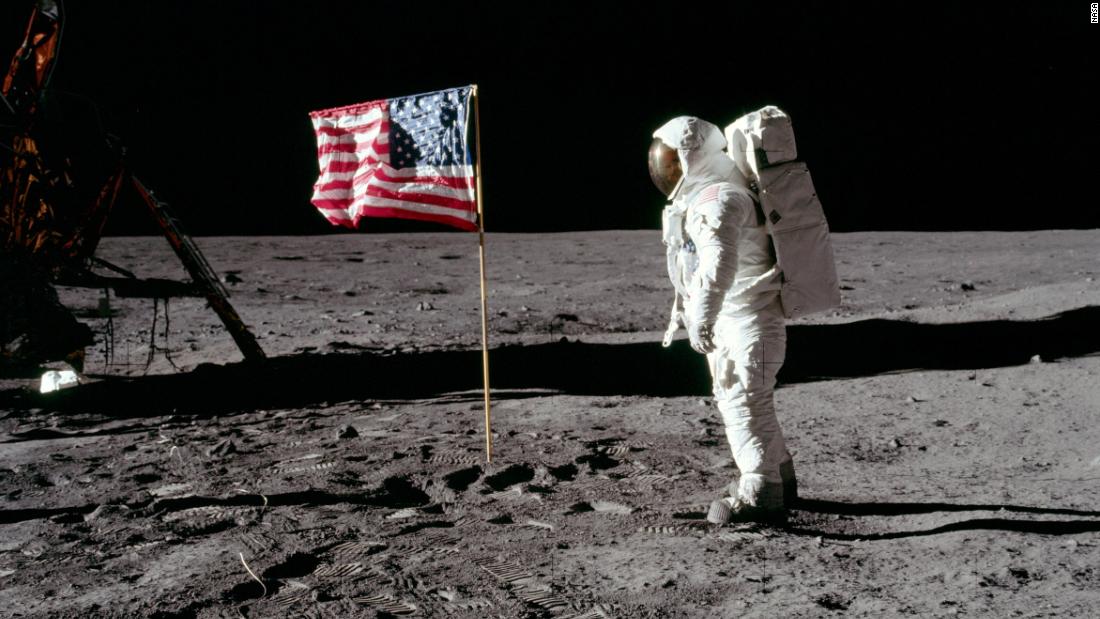

While it would be nice to think that a human community on the moon would be a collaborative, multinational utopia – although it is located in what Buzz Aldrin famously described as a “wonderful desolation”, the fact that humans are each other again chasing to reach our moon neighbor.

The American Artemis project, which aims to send the first woman to the moon in 2024, is the most ambitious mission. Russia has relaunched its Luna program and set the stage to place cosmonauts on the moon in the 2030s. However, in a race that was once reserved for superpowers, there are now several countries and several private companies with an interest.

India plans to send a rover to the Moon this year. China, which in December implemented the first successful lunar return mission since 1976, announced several lunar landings in the coming years, with the Chinese media’s plans for a mission to the moon within a decade. South Korea and Japan are also building lunar landers and probes.

READ MORE: Sleeping walls can be the key to cryogenic sleep for human space travel

Private companies such as Astrobotic, Masten Space Systems and Intuitive Machines are supporting NASA missions. Other companies, such as ispace, Blue Moon and SpaceX, are also supporting NASA missions, but are also offering private missions, including for tourism. How are all these different entities going to work around each other?

Space is not lawless. The 1967 Spatial Convention, now ratified by 110 countries, including all current spatial countries, provides guiding principles that support the concept of space as the province of all mankind. The treaty explicitly states that all countries and, by implication, their subjects have the freedom to explore and release all areas of the moon.

That’s right. Everyone has the freedom to wander where they want – over Neil Armstrong’s shotprint, close to sensitive scientific experiments or to a mining industry. There is no understanding of property on the moon. The only restriction on this freedom is the emphasis in Article IX of the Convention that all activities on the moon must take into account the corresponding interests of all others and the requirement that you consult with others if you can cause “harmful interference”.

What does it mean? From a legal point of view, no one knows.

READ MORE: How nine days underwater help scientists understand what life will be like on a lunar basis

Outstanding universal value

It can be reasonably argued that interference with an experiment or a lunar mining operation would be harmful, cause quantifiable damage and thus violate the treaty.

But what about an abandoned spacecraft, like the Eagle, the Apollo 11 lunar lander? Do we really want to rely on ‘proper consideration’ to prevent the intentional or unintentional destruction of this inspiring piece of history? This object commemorates the work of hundreds of thousands of individuals who worked to place man on the moon, the astronauts and cosmonauts who gave their lives in this quest to reach the stars, and the silent heroes, such as Katherine Johnson, who math that made it so.

The lunar landing sites – from Luna 2, the first man-made object to hit the moon, to each of the crew of Apollo missions, to Chang-e 4, which deployed the first rover on the other side of the moon. especially testifies to mankind’s greatest technological achievement to date. It symbolizes everything we have achieved as a species, and holds such promises for the future.

The One Small Step Act is true to its name. This is a small step. This only applies to companies that work with NASA; it only applies to US lunar landings; it implements outdated and untested recommendations to protect historic lunar sites implemented by NASA in 2011. However, it offers significant breakthroughs. It is the first legislation of any nation that recognizes an outside world website as ‘outstanding universal value’ for mankind, the language derived from the unanimously ratified World Heritage Convention.

The law also encourages the development of best practices to protect human heritage in space by developing the concepts of proper consideration and harmful interference – an evolution that will also guide the way nations and societies work around each other. However small it may be, the recognition and protection of historic sites is the first step in developing a peaceful, sustainable and successful lunar management model.

The boat prints are not yet protected. There is a long way to go to reach an enforceable multilateral / universal agreement to govern the protection, preservation or commemoration of all human heritage in space, but the One Small Step Act should give us all hope for the future in the space and here on earth.

READ MORE: Bats and unicorns – in the original moon box

Michelle LD Hanlon is a professor of aerospace law at the University of Mississippi.