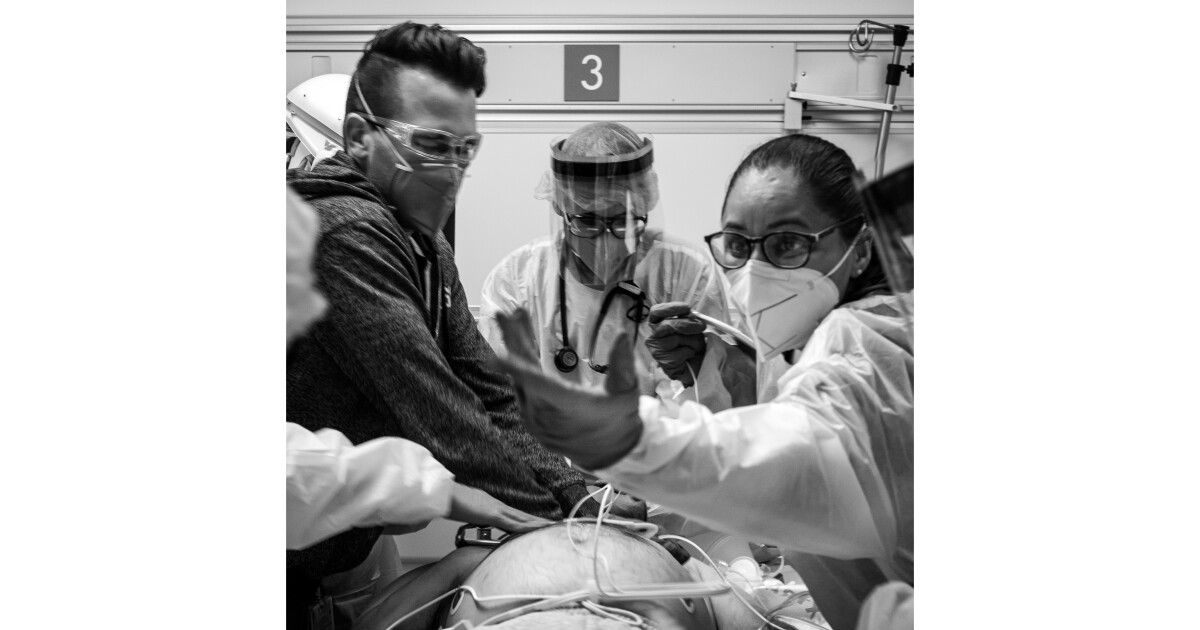

From behind her face shield the young doctor stared straight ahead.

She is standing behind a COVID-19 patient lying on an operating table. A vital monitor shows that the man’s heart is beating and he is taking 47 breaths per minute – doubling the normal pace. A nurse’s glove extends over him and holds a syringe.

In the black-and-white photo, the doctor’s eyes are wide.

The person who captured the moment does not have to ask why.

Dr. Scott Kobner outside LA County-USC Medical Center in Boyle Heights. When the COVID-19 pandemic began last spring, and devastated Kobner’s home state of New York before it flared up in California, he knew history was unfolding.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

Dr. Scott Kobner, the 29-year-old resident of the Department of Emergency Medicine at USC Medical Center in Los Angeles County, knew it was the moment of silence just before an intuitive patient was placed in a medically induced person. . coma from which he may not wake up.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began last spring, and devastated Kobner’s home state of New York before it flared up in California, he knew history was unfolding. Soon he began to show up in his free days in the hospital with instruments that felt just as important in the growing moment as his stethoscope: his Leica M6 and M10 cameras.

Medical photography has a great tradition dating back to the Civil War, when doctors captured black-and-white images of bullet wounds and gangrene and cut off limbs, showing in unprecedented detail the brutality of the war.

Clinical photographs from World War I showing parts of soldiers’ faces blown off by machine guns were invaluable to surgeons learning how to literally reconstruct faces. Nowadays, documentary photographs of the flu pandemic of 1918 – the first major outbreak of which was on a military base in Kansas amid the war – are treasures of the COVID-19 era.

The pandemic is not a conventional war, but in its own way it is a battle with its range of infantry – doctors, nurses, first responders – and a front line that is changing, in intensity and dimension, hope and despair, as much as a battlefield.

Kobner was determined to document it at County-USC, one of the country’s largest public health systems.

“There is a narrative authority of photography,” he said. ‘People just unequivocally accept a picture as a moment of reality that we have to interpret. … There are many delights involved in taking these types of photos, and you should have the utmost respect for the human dignity and condition of those involved. ”

Dr Daria Osipchuk looks at her team for the last time before intubating a young man in COVID-19 in severe respiratory distress.

(Scott Kobner)

Dr Daria Osipchuk was shocked when she first saw Kobner’s photo of her big eyes, the only part of her face visible above her N95 mask. She has never seen a photo of her work.

“It was a bit haunting to look and see in my own eyes. In my eyes, I see the moment of calm before the intubation and the seriousness of the situation,” said Osipchuk, a 29-year-old resident.

Medical illustrations have been used as a teaching tool for hundreds of years. But the use of photography to document human crises increased during the Civil War, especially after the Army Medical Museum was established in 1862 to collect artifacts and images for battlefield medicine research.

Reed Bontecou, a New Yorker who became a surgeon at Harewood Hospital in Washington, DC.

He took portraits of wounded soldiers and marked them as a learning instrument with a red pencil to show the trajectories of bullets. Veterans later used the photos to prove the severity of their injuries while applying for state pensions.

Bontecou took close-ups of gangrenous wounds and documented the use of anesthesia. One of his images, titled “Field Day,” shows a stack of amputated feet and legs outside the hospital just before it was burned, said Mike Rhode, an archivist at the U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery.

Doctor photos were useful for documenting human tragedies and for clinical use, showing doctors what types of wounds they treat.

‘It’s not just a professional photographer looking for a bloody story; it’s an insight perspective, ”says Jim Connor, a professor of medical humanities and the history of medicine at the Memorial University of Newfoundland.

While dr. Molly Grassini resuscitates a patient in cardiac arrest, she stares at the heart monitor during a pulse check and hopes that her patient shows any signs of life.

(Scott Kobner)

‘It gives insight to the general public – this thing is genuine. … It gives some truth and truthfulness when the doctor or nurse takes the pictures. ‘

Kobner, the son of two police officers, said he is always involved in public service. Emergency medicine – which he describes as “the crossing of human conditions: socio-economics, the terrible conditions of our biology, the things we as human beings cannot control” – fits the bill. He is studying at the University of New York and living his dream as a resident of County-USC, the 600-bed public hospital in Boyle Heights.

When New York became an early center of the pandemic last spring, Kobner recognized the doctors on the news as hospitals were flooded with cases of coronavirus. They were his friends and medical instructors, the people who taught him to use a ventilator.

Kobner felt guilty. Cases have not yet exploded in Southern California, and his hospital has had time to prepare. The emergency room at County-USC was horribly empty when people stayed home and avoided hospitals.

“It was very whimsical for all of us,” Kobner said. “We had never heard the silence of our hospital at that time.”

The first boom came in early summer. Then Kobner treated his first very ill COVID-19 patient. He still thinks of her a lot.

A crew of firefighters in Los Angeles, amid a sleepless 24-hour shift, give a report to a County-USC emergency doctor on the ambulance ramp. Inside, the rest of the ER team prepares a bed for the critically ill COVID patient.

(Scott Kobner)

She was a lovely woman in her 50s, with wavy brown hair and a big smile. She had a fever and was drenched in sweat, but joked that Kobner, under all his personal protective equipment, had to be hotter than she was.

She came to the emergency room at the beginning of a busy shift and quickly refused. Intubation was her last option, even if it was not a good option, Kobner said.

It was the first time Kobner had to prepare a family speech with a loved one about FaceTime before intubation, the first time he had to say that this might be the last chance to talk to them.

The woman’s daughter asked Kobner what she should say. He told her what he would say to his mother or father or sister: that he really loved them, that he was sorry he could not be there, but that he was just on the other end of the phone. He would tell them how glad they made him.

When the medical team prepared to intubate her, everyone had tears in their eyes.

“You have a full mask and gown,” Kobner said. “You can not wash it away. They just hang there. I think of her a lot because it did not get easier hundreds of conversations later. ”

The woman is dead.

Kobner only takes photos on his free days and makes it clear to patients that he is not involved in their care. According to him, the hospital gave permission to take pictures due to the historical nature of the pandemic, and he gets permission from each patient.

Dr. Nhu-Ngyuen Le, right, oversees Dr Chase Luther as he places an emerging central line, a device that can deliver life-saving medicine into the largest veins of the body.

(Scott Kobner)

Kobner said he has a duty to pick up his camera because there has been so much suffering under the pandemic behind hospital walls, mainly from the point of view of a public that can more easily believe not what he cannot see.

“I think the recognition of humanity and the real human struggle we do every day has a much more profound impact than a campaign with great graphics or powerful evidence,” he said.

During the summer, Kobner tested positive for the coronavirus and was ill for about ten days and was in bed most of the time. He lives alone – to isolate a blessing and a curse in such times. He feels happy that he does not have to be admitted to the hospital.

But he said the winter push was worse. There was a feeling of helplessness for weeks on end. No matter how many patients he saw during a shift, he knew he would see just as much the next day.

“In emergency medicine, we are used to seeing so many different complaints: heart attack, gunshot wound, broken arm,” he said. “But during the boom, it was the same story over and over again.”

In December, he started posting some of the photos on Instagram with captions that are clinical, melancholy, frustrated and hopeful.

There’s a picture of a woman lying on her stomach in her hospital bed, a tube in her nose. Her eyes are sad.

“Isolation, quarantine, loneliness: words that are now included in our daily vocabulary. “When Ms H told me how alone she felt, at home before she got sick and was now fighting in the hospital with COVID, I can only share a dream of a better future with her,” he wrote. “To go back to a time when I could hold her hand while we talked without a latex glove or a plastic dress separating us from human touch.”

In another darkly lit shot, a doctor bends over a patient’s head and holds a suture scissors after drilling a hole in the woman’s skull.

Polaroids from LA County-USC Medical Center staff hang next to boxes of gloves and masks in the room just outside the COVID-19 unit. After putting on their personal protective equipment, vendors stick these self-portraits on their gowns to show the faces of the people caring for them.

(Scott Kobner)

“Strokes and intracranial hemorrhages are potentially devastating complications of this infection that are heartbreaking to behold,” Kobner wrote. “A drain inserted through the skull into the brain relieves the accumulation of pressure associated with intracranial hemorrhage, and the drainage that emerges can be life-saving for patients.”

Another shows a wall just outside the COVID-19 unit, where Polaroid self-portraits of smiling doctors and nurses hang next to boxes of gloves and masks. They pinned the photos on their gowns to show patients what they look like under the glasses and face mask.

According to him, the ritual decreased as the appearance of personal protective equipment became normal.

“Some of these faces I have not seen for months without a mask,” he wrote. ‘Their smiles look so real and full of life – eager and hopeful. They look so different from the eyes I see daily: full of fear, fatigue and sadness.

“These photos were for the patients, but now I think they are for us.”