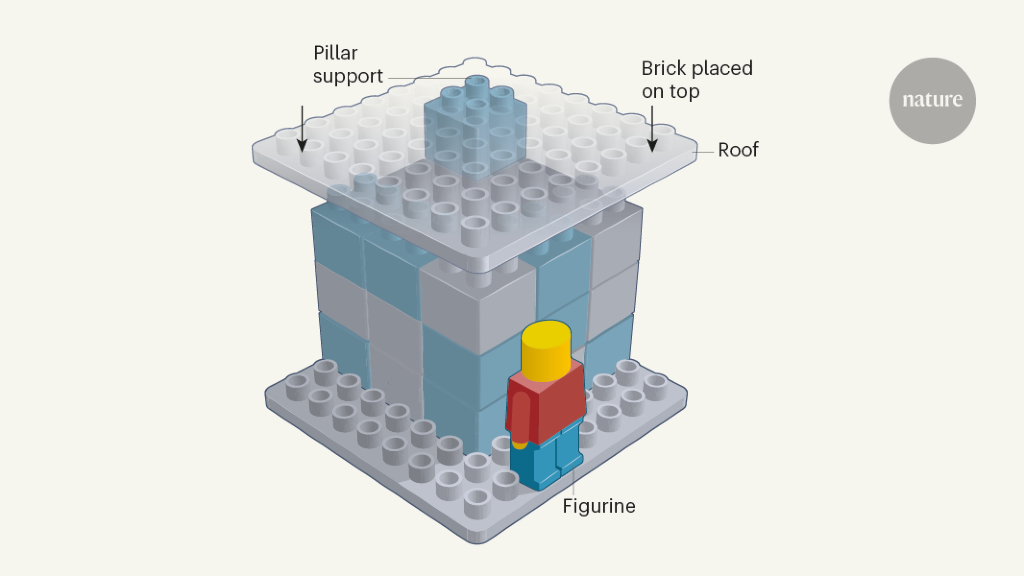

Consider the Lego structure depicted in Figure 1, in which a statue is placed under a roof supported by one pillar at one corner. How would you change this structure so that you could place a brick against it without smashing the figurine, considering that each block added costs 10 cents? If you’re like most participants in a study reported by Adams et al.1 in Nature, you would add pillars to better support the roof. But a simpler (and cheaper) solution is to remove the existing pillar and let the roof rest on the base. Over a series of similar experiments, the authors observe that people consistently consider changes that add components over those that subtract them – a trend that has broad implications for everyday decision-making.

For example, Adams and colleagues analyzed archive data and observed that only 11% of responses were involved in removing an existing regulation, practice, or program when an incoming university president requested amendments to enable students to and better serve community. . Similarly, when the authors asked study participants to make a 10 × 10 grid of green and white squares symmetrical, participants often added green squares to the empty half of the grid instead of removing them from the grid. remove full half, even when the latter would have been done more efficiently.

Adams et al. showed that the reason why their participants offered so few deduction solutions was not because they did not recognize the value of these solutions, but because they failed to consider them. Indeed, when instructions explicitly state the possibility of deduction solutions, or if participants had more opportunity to think or practice, the likelihood of offering deduction solutions increased. So it seems like people tend to apply ‘what can we add here’? heuristic (a standard strategy to simplify and speed up decision-making). This heuristic can be overcome by making extra cognitive efforts to consider other, less intuitive solutions.

While the authors focused on the participants’ failure to even consider deduction solutions, we suggest that the bias toward additive solutions may be further exacerbated by the fact that it is less valued to deduct. People can expect to receive less credit for solutions that deduct than added solutions. A proposal to get rid of something may feel less creative than adding something new, and it can also have negative social or political consequences – suggesting that an academic department is disbanded may not be appreciated by those who do not work in it, for example. In addition, people may assume that existing features are there for a reason, and thus can look for supplements more efficiently. Finally, the bias of solar costs (a tendency to continue when an investment in money, effort or time has been made) and waste disposal can lead people to shy away from removing existing features2, especially if the features made an effort to create in the first place.

These perceived disadvantages of deductible solutions may encourage people to seek out additives on a regular basis. This is consistent with the suggestion of Adams and colleagues that regular earlier exposure to additive solutions made them more cognitively accessible and therefore more likely to be considered. In addition, we suggest that previous experience may lead people to assume that they are expected to add rather than subtract. As a result, study participants may generally generalize from past experiences and instinctively assume that they should add features, and only revisit this assumption after further reflection or explicit calls. Similarly, members of a university community can implicitly accept that the incoming president wants them to formulate new initiatives and not criticize existing criticisms.

What are the implications of Adams and colleagues’ findings? There are many consequences in the real world if you do not take into account that situations can often be improved by removing rather than adding. For example, if people feel dissatisfied with the decor of their home, they can address the situation by going on an expense and purchasing more furniture – even if it’s just as effective in getting rid of a cluttered coffee table. Such a trend can be especially pronounced for consumers who do not have resources, which are especially aimed at obtaining material goods3. This not only harms consumers’ financial situations, but also increases the pressure on our environment. On a larger scale, the favoring of additive solutions by individual decision makers can contribute to problematic societal phenomena, such as the increasing expansion of formal organizations.4 and the almost universal, but environmentally unsustainable, pursuit of economic growth5.

The work of Adams and colleagues shows a way to avoid these pitfalls in the future – policymakers and organizational leaders can express and appreciate suggestions, which diminish and do not add. For example, the university president may specify that recommendations to remove committees or policies are expected and appreciated. In addition, both individuals and institutions can take self-control measures to guard against the standard tendency to add. Consumers can reduce their storage space to limit their purchases, and organizations can specify sunset clauses that can enable the automatic shutdown of initiatives that do not meet specific goals.

It is noteworthy that a prejudice on addition will always apply. In some situations, it should probably be easier to generate subtractive changes because it is not necessary to suggest something that is not yet there. Indeed, when people imagine how a situation might turn out differently, they are more likely to do so by undoing an action they did rather than adding an action they could not undertake. .6. As we move forward, it will be worth exploring when we are willing to imagine ourselves removing events, just imagining the removal of features, thus helping us solve problems by subtraction.