Wherever you look in West Antarctica, the message is the same: the glaciers that end the navy are melting through warm seawater.

Scientists have just observed the ice currents in the ocean along a 1,000 km long coastline known as the Getz region.

It contains 14 glaciers – and they have all accelerated.

Since 1994, they have lost 315 gigatons of ice, equivalent to 126 million Olympic-sized pools of water.

If you put it in the context of the contribution of the Antarctic continent to the global sea level rise during the same period, Getz is just over 10% of the total – a little less than a millimeter.

“This is the first time anyone has done a very detailed study of this area of West Antarctica. It is very inaccessible for people to go and do fieldwork because it is so mountainous; most of it has never been trampled by humans, “explains Heather Selley, a glacier at the Nerc Center for Polar Observation and Modeling at the University of Leeds, UK.

“But it’s very important that we understand what’s going on there – to realize that its glaciers are accelerating and why,” she told BBC News.

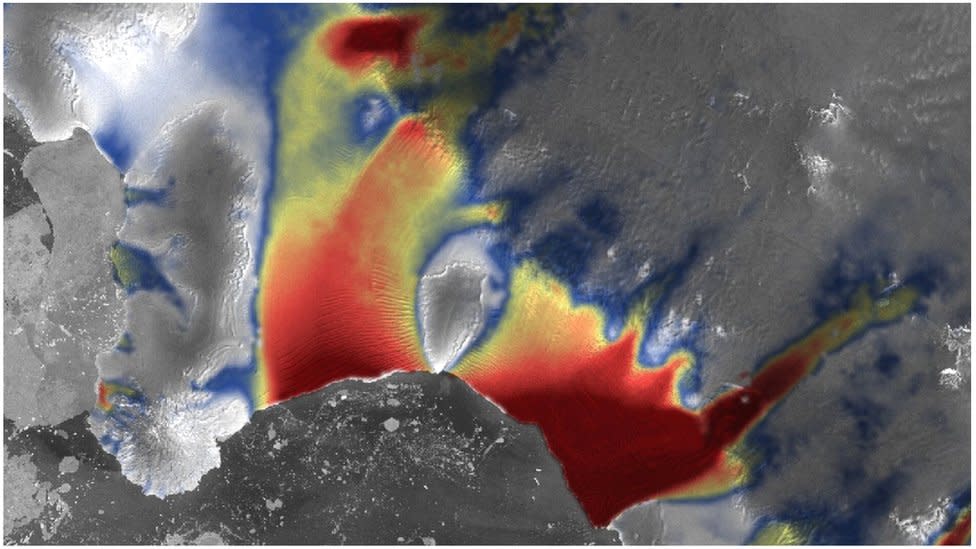

Selley and colleagues examined two-and-a-half decades of satellite radar data on ice velocity and thickness. In this analysis, they added information on ocean properties immediately off the coast of Getz – along with the outputs of a model that puts the local climate in context during the period.

The findings, published in the journal Nature Communications, show an unambiguous linear trend.

On average, the speed of all 14 glaciers in the region increased by almost a quarter between 1994 and 2018, with the velocity of three central glaciers increasing by more than 40%.

One specific ice flow was found to flow 391 m / year faster in 2018 than in 1994 – an increase of 59% in just two and a half decades.

The probable cause is again what researchers call ‘ocean coercion’. Relatively warm deep ocean water comes under the floating fronts of the glaciers and melts it from below.

Pierre Dutrieux, co-author of the British Antarctic Survey, said: ‘We know that warmer ocean waters erode many of the West Antarctic glaciers, and these new observations show the impact they have on the Getz region.

“This new data provides a new perspective on the processes that are taking place so that we can predict future change with more certainty.”

Where a line of glaciers juts out into the sea, their floating fronts will often merge into a single, continuous platform called an ice shelf. It is interesting to note that in the case of Getz this platform gains a certain stability by pressing against eight islands and a number of shallow points on the seabed.

And yet, even with this built-in stability, the nourishing glaciers melt behind and accelerate.

Co-author Anna Hogg, also from Leeds, is an expert on satellite remote sensing in the polar regions.

She told BBC News: “We have observations around the entire ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica in a way we have never had before. We can map out really detailed, localized patterns of change.

“We understand how ocean water moves around under the ice shelf – how and where it enters the cavity under the shelf, so that we can really bind the physical process of ocean coercion to the signal we see in the satellite data.”