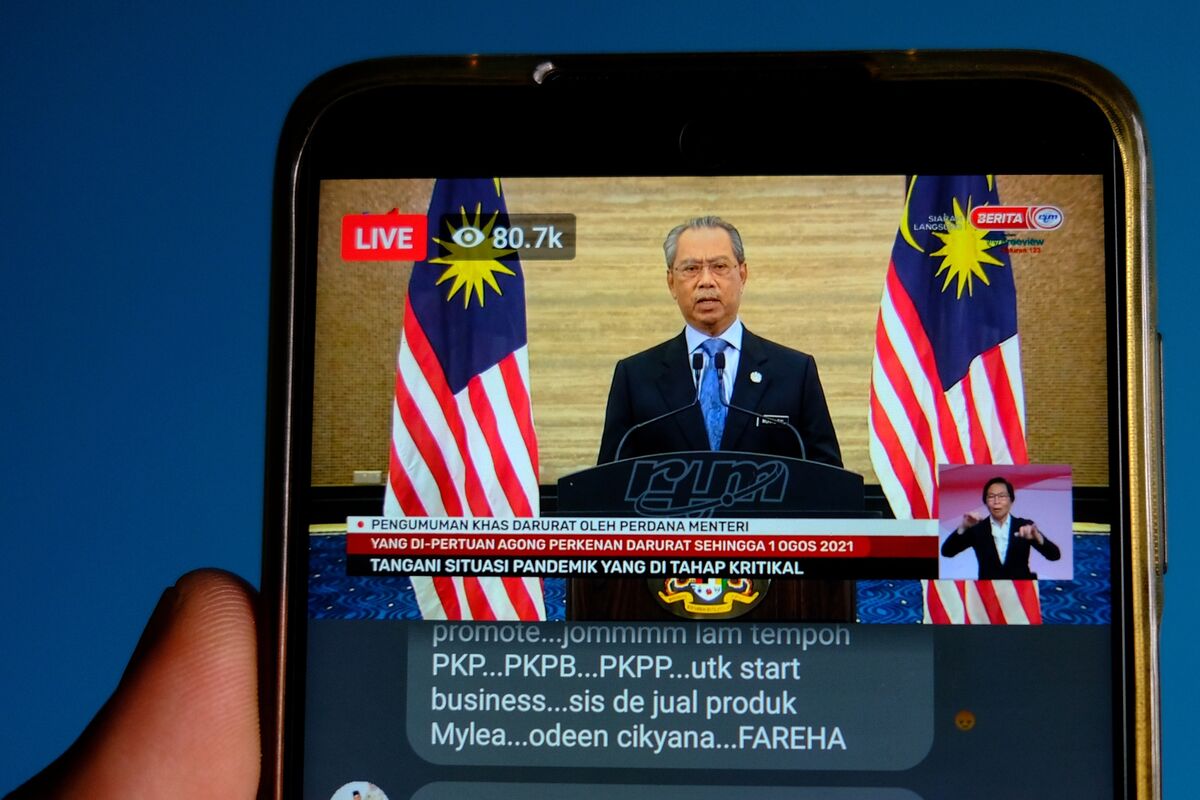

Muhyiddin Yassin during a live news broadcast on January 12.

Photographer: Samsul Said / Bloomberg

Photographer: Samsul Said / Bloomberg

In declaring why Malaysia had to suspend democracy for the first time in half a century to fight the pandemic, Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin assured the country that he was not carrying out a military coup.

But his opponents found it difficult to view the first nationwide emergency since 1969 as a mere force attack. While the country in Southeast Asia has seen an increase in coronavirus cases in recent weeks along with many other countries, measures to combat the pandemic have generally enjoyed great support in the political spectrum.

“Do not hide behind Covid-19 and burden the people with an emergency statement to save yourself,” Pakatan Harapan, the largest opposition bloc in parliament, said in a statement after the announcement.

The only problem that could be easily solved by the emergency was Muhyiddin’s political trouble: some key leaders in the ruling coalition’s biggest partner, United Malays National Organization (UMNO), recently called for a new election as soon as possible. Now, with parliament possibly suspended until August, the prime minister does not have to worry about an election anytime soon.

While the move brings stability to Malaysia for the first time since political infighting overthrew a coalition government early last year and lifted Muhyiddin to power, it also poses a risk to the country’s democracy. Before the last election in 2018, the same ruling coalition ruled for about six decades – often with hardship tactics that the media and opposition politicians wanted to silence.

Malaysia last experienced a nationwide state of emergency in 1969, when racial riots between ethnic Malays and Chinese led to the suspension of parliament for two years. According to Oh Ei Sun, a senior fellow at the Singapore Institute of Singapore, the state of emergency is ‘totally unnecessary’ because the criteria for imposing one have not been met and ‘no sensible MPs’ from either party will times to end the pandemic. Foreign Affairs.

“If you are not careful, we will turn parliamentary democracy into a rule of dictation,” he said. “It’s addictive – future governments will once again call for a state of emergency.”

Investors were cautious after the announcement, with the ringgit and the country’s main stock index falling on Tuesday. A close announcement on Monday prompted Fitch Solutions to reduce Malaysia’s 2021 economic forecast for 2021 to 10% from 11.5% earlier, while warning that restrictions could last months.

For the 73-year-old Muhyiddin, a former UMNO stalwart who has gambled by switching over his four-decade political career, this is a welcome opportunity to consolidate power. Since becoming prime minister in March 2020, he has been under constant pressure from both his 12-party coalition and an opposition led by Anwar Ibrahim, who has repeatedly claimed he has the numbers to form a new government.

In October, the King of Malaysia rejected his push to declare an emergency, which would enable him to avoid a budget vote in parliament, which could also serve as a confidence test. But he survived, and the recent increase in virus cases – which reached a record 3,309 on Tuesday – enabled him to persuade the king to grant emergency powers this time.

“This period of distress will give us the necessary calm and stability,” Muhyiddin said in a televised speech to the country on Tuesday. He added that the decision “is not a military coup and the curfew will not be enforced.”

‘Chess mat’

After the emergency, one UMNO legislator became the second in the last few days of the group declaring that he was withdrawing support from Muhyiddin. The party as a whole was more reticent, with President Ahmad Zahid Hamidi saying the prime minister should use his emergency power only on measures containing the pandemic and restore parliamentary practices as soon as possible.

“Muhiyiddin Yassin is safe now,” Awang Azman Awang Pawi of the University of Malaya. “When the state of emergency was declared, UMNO was checked because nothing significant could be done during a state of emergency.”

Photographer: Samsul Said / Bloomberg

Muhyiddin was vague about how he was going to use his new powers. On Tuesday, he warned of possible price controls, greater control over public hospitals and a role for the military and police in instituting public health measures. He also promised to hold an election once an independent committee has declared that the pandemic has subsided and that it is safe for voters to go to the polls.

Whether Muhyiddin’s Bersatu party will win in the next election depends largely on how he handles the virus during the period of emergency rule. So far, he has failed to find solutions to stem the tide in cases – an outcome that ironically laid the groundwork for him to implement the emergency and keep his opponents at bay.

“Without a strategy to address Covid-19, they are using these leverages to hold on,” said Bridget Welsh, honorary research fellow at the Asia Research Institute, University of Nottingham Malaysia. “It is a reflection of the instability and ultimately it will exacerbate the divisions and divisions in a highly polarized society.”

(Updates with more Muhyiddin comments in the 11th paragraph)